TREVOR B. POOLE

Universities Federation for Animal Welfare

The Old School, Brewhouse Hill,

Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8AN

INTRODUCTION

Marmosets and tamarins are small (250-500 g) South American monkeys of the family Callitrichidae. They are forest living species with squirrel-like locomotion and, unlike typical monkeys, most of the digits have claws instead of nails. They live in small troops, most members of which are closely related; there is one breeding female and usually several other adult non-breeding females. There is some controversy among field workers as to whether they are monogamous or polyandrous (several males mating one female). The single breeding female has been observed, in the wild, to mate with several males in the troop, but it is not known whether matings with males other than the dominant proved fertile.

The natural food of marmosets and tamarins consists of fruits, nectar, shoots and insects, young birds and bird's eggs. The animal protein intake is high. The short tusked marmosets (Callithrix and Cebuella) feed extensively on the gum produced by some species of forest tree which they access by gouging with a scoop formed by the lower incisors and shortened canine teeth. The tamarins (Saguinus and Leontopithecus) do not gouge but may feed opportunistically on gum oozing from wounds on trees. Field studies have shown that callitrichids spend up to 60 per cent of their time actively foraging.

Unlike other monkeys, marmosets give birth to two or more young in a litter. Parental care, which includes carrying, grooming and sharing food with infants, is undertaken by all adult and adolescent members of the troop.

The potentiality for using marmosets as breeding animals for biomedical research is well recognised and there are now numerous laboratory breeding colonies. Where the marmoset is a suitable model, its small size and high reproductive capacity have proved valuable assets, and the common marmoset is the only species of monkey used in the laboratory where supply is totally independent of wild caught stock.

There are of course some disadvantages to the marmoset, it is monogamous under captive conditions, so that equal numbers of males and females have to be kept in the breeding colony. Although marmosets are rarely capable of rearing more than two young, in over 60 per cent of captive births more than two young are born; in the case of triplets, supplementary feeding or hand rearing may be used to promote the survival of all three young. While triplets are commonest, females have been known to give birth to as many as five infants. Where there are four or five in a litter, however, they are usually undersized and fail to thrive. In indoor facilities the diet must be supplemented with vitamin D3 or an ultra-violet light source be provided.

These facts will probably be familiar but they form an essential background to any discussion of environmental enrichment in marmosets.

THE NEED FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ENRICHMENT

Many mammals, and probably some of the more intelligent birds, are known to suffer if their environment is too restricted. The evidence that their behavioural needs are not being met is based on the occurrence of abnormal behaviour in the form of inactivity, apathy or stereotyped behaviours such as pacing or running around in circles.6 These symptoms are most pronounced where primates are housed singly and the emotional state of the animal can best be described as boredom.

In nature, a marmoset leads a busy and varied life; it is adapted to a complex environment and foraging alone is elaborate and involves the selection of seasonally varying vegetable food items and hunting insect prey. Survival depends on skill and ingenuity and constant vigilance to identify aerial, arboreal and ground predators, which may be mobbed. Marmosets have a wide repertoire of vocalisations which they use to convey messages both within and between troops.

The commonly used metal laboratory cage 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.8 m with a feeding trough and a watering point makes a stark contrast to the natural habitat. Clearly, it is not possible to recreate a tropical forest in a laboratory and yet a bare, small cage is clearly inadequate. First we must specify the aims of environmental enrichment and, secondly, examine the needs of the animal and finally, the means by which improvements can be made.

THE AIMS OF ENVIRONMENTAL ENRICHMENT

The objective of environmental enrichment is to meet the animal's behavioural needs. It can be shown that these needs have been met if the primate shows a rich behavioural repertoire and there is an absence of abnormal behaviours.

The obligation to meet the behavioural needs of non-human primates has been incorporated into legislation in both the European Community ('ethological needs') and the United States ('psychological well-being'). The author prefers the term behavioural needs because it is less ambiguous and more easily understood!

THE BEHAVIOURAL NEEDS OF MARMOSETS

The needs to be listed are not peculiar to marmosets and are certainly shared by all higher social primates (see the recent review of environmental enrichment by Chamove1).

The need for companions

Few marmosets are kept singly in cages because they soon lose condition and, if not socially housed, often die. For special experimental paradigms such as metabolic studies short periods of isolation of no more than 30 days have been used. Where an adult marmoset is unpaired, for example, as a result of an unequal sex ratio, in the Aberystwyth colony we successfully paired individuals of different species together (for example Callithrix jacchus and C. argentata), and found they were tolerant and spent time grooming and sitting together in the manner typical of conspecifics.

For breeding purposes, marmosets are normally kept in family groups of 2-8 individuals. Under these conditions they spend much time grooming one another, playing, displaying to other groups and caring for young. They are thus kept quite busy and there is always a social role for the individual.

The only real problem encountered with the social housing of marmosets is the keeping of groups of non-breeding individuals. Same sex individuals kept together may fight and often one individual is bullied and needs to be removed. This problem may be avoided by using a very large cage with complex furniture and plenty of escape routes. Very careful monitoring is essential and this places a great responsibility on the technician in day-to-day charge. It is always possible to keep same-sex twins together so that this can solve the problem of keeping non-breeding individuals in a social environment. If breeding is restricted to individuals from opposite sex twin litters then both breeding and stock situations can be satisfied. From published data7 there does not appear to be a tendency for females to give birth predominantly to either same or opposite sex twins; so that these traits are unlikely to be selected by this system.

The need for space and complexity

An important point must be made, namely, that usable space from the standpoint of the marmoset, is not synonymous with cage size. Empty space is virtually useless; a metal box with smooth sides is just a floor! Often one hears the question 'Shall we give them more space?' The question really should be 'If we give them more space what extra things can we provide for them to do in it?'

The construction of the cage plays an important part in environmental enrichment for marmosets. Marmosets live in a three dimensional habitat where height is of essential importance and, in accordance with this principle, a number of laboratories are now using a 'sentry box' type of tall cage.5 All monkeys prefer to look down on potential ground predators, of which we humans are one. Another welcome improvement is that a number of commercial laboratories are constructing wooden cages to their own design. Such 'soft' environments are much healthier, for example condensation is reduced, and dimensions are much more flexible. The old metal cages meet the needs of the sterilizer rather than the monkey.

In determining the size of a marmoset cage the linear dimensions should allow for the animal to show its natural locomotor repertoire. This involves running, jumping (at least its own body length), pouncing, hanging upside down by the hind legs and rough and tumble and locomotor play. Perching above human eye level is also desirable. Allowing for a family group of up to eight individuals, the provision of these spatial requirements can be quite inexpensive.

The provision of good cage furniture is essential for environmental enrichment. Wooden dowelling, branches of trees, flat perches and feeding sites are standard these days but marmosets also greatly appreciate trapezes, these can be in the form of dowelling suspended on two chains or a vertical dowelling screwed into the centre of a square flat piece of plywood and suspended from the cage ceiling. Such swings are incorporated into locomotor play and their unpredictable responses to being jumped upon encourage the monkey to practise its locomotor skills. Flexible hosing may also be of value in that it simulates a liana in the forest. The mesh walls and ceiling of the cage will also provide both ventilation and footholds for active locomotion. An elevated feeding site should also be provided.

The need for an element of unpredictability in the environment

One of the problems of confinement is the sameness and predictability of the enclosed environment. This leads to boredom so that an element of unpredictability is of value from the standpoint of marmoset welfare.

It is now accepted by the majority of those concerned with housing non-human primates that a woodchip substrate with food concealed in it is both hygienic and provides the monkey with beneficial opportunities for foraging.2 The interesting fact is that marmosets and other monkeys will actually work to find hidden food when similar food is available in abundance at a feeding point; they seem to gain satisfaction in searching for food scattered unpredictably. This attribute is of great value because it can be used to simulate the 60 per cent of time spent in the wild on foraging, thus increasing natural behaviour. Also it does not interfere with the provision of a balanced diet. Marmosets, like other primates, appreciate a varied and interesting diet offering some degree of choice.

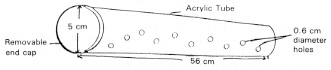

Zoos have found that providing food unpredictably in time can also be highly beneficial. Shepherdson9 devised a simple 'mealworm dispenser' which releases mealworms at random. Its design is simple (see Figure 1), consisting of a transparent acrylic tube with holes drilled in it; the tube is filled with mealworms and sawdust and corked at each end. The mealworms from time to time fallout and are found by the predator.

The need to exercise some control over the environment

Having established that marmosets like to work, it is hardly surprising that they also like situations where they have some control over their environment. They appear (to quote from the classic work on animal play by Karl Groos3) to 'take pleasure in being a cause' .The most effective techniques are undoubtedly those in which there is likely to be a food reward. Toys alone tend to be ignored once the novelty has worn off.

Marmosets like wood to gnaw and gouge they also strip bark off branches, facilities to do this can easily be provided. McGrew4 even invented an 'artificial gum tree'. This was constructed from 50 cm of 4.7 cm diameter hardwood (tamin) dowel. The dowel was cut into 7 cm lengths and each section was drilled to provide four gum reservoirs of 0.9 cm diameter and a continuous central hole through which a threaded brass rod was passed. A wooden cap sealed the open end of the last reservoir and the whole was secured with wingnuts and washers. The reservoirs were filled with gum arabic and the marmosets had to gouge holes to release the gum.

Hanging whole fruits, such as bananas or oranges, in the cage, providing that initially a small piece of rind is stripped off, will enable the marmosets to feed naturally. Another simple device, available from most pet shops for garden birds, is the suspended feeder, which contains peanuts or raisins and can only be reached by hanging from a perch or the ceiling. Such a device can easily be constructed from a hollowed out log with holes slightly larger than a peanut drilled in it. In the Aberystwyth marmoset colony we found that marmosets liked almost empty yoghurt cartons, after eating the contents they would run round the cage with the carton on their heads!

Where it is necessary for a specific reason to keep a marmoset alone in a cage, training apparatus can prove useful.8 Variable schedule lever pressing to obtain food rewards, music or television will all be utilised by the animal. Co-ordination can be put to the test by placing a moving belt with pieces of apple on it immediately in front of the cage. A variable speed motor will provide different requirements of skill on the part of the monkey. In most cases, however, there will be no need to resort to such elaborate technology to provide environmental enrichment for captive marmosets.

CONCLUSIONS

Marmosets are among the easiest of primates to provide with environmental enrichment. Like other higher primates, they need four conditions:

Companionship

Adequate space with incorporated complexity

Some unpredictability in the environment

Ways in which they can manipulate or control their environment

To provide these forms of environmental enrichment for marmosets is practicable and inexpensive. Because of their greater spatial requirements it is more difficult and costly to provide a good laboratory environment for larger species such as cynomolgus, rhesus monkeys or baboons. Where they are suitable, therefore, marmosets should be used in the laboratory in preference to larger species of monkey.

References

1. Chamove, A. S. (1989). Environmental enrichment: a review. Animal Technology, 40: 155-178.

2. Chamove, S., Anderson, J. R., Morgan-Jones, S. C. and Jones, S. P. (1982). Deep woodchip litter: Hygiene, feeding and behavioural enhancement in eight primate species. lnt. J. Stud. Anim. Prob. , 3: 308-318.

3. Groos, K. (1898). The Play of Animals. New York, Chapman and Hall.

4. McGrew, W. C., Brennan, J. A., and Russell, J. (1986). An artificial "gum tree" for marmosets (Callithrix j. jacchus). Zoo Biology, 5: 45-50.

5. Plant, M. and Burt, D. (1983). Observations on marmoset breeding at Fisons. Animal Technology, 34: 29-36.

6. Poole, T. B. (1988). Normal and abnormal behaviour in captive primates. Primate Report, 22: 3-12.

7. Poole, T. B. and Evans, R. G. (1982). Reproduction, infant survival and productivity of a colony of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus jacchus). Laboratory Animals, 16: 88-97.

8. Scott, L. (1990). Training non-human primates—meeting their behavioural needs. In Animal training. Symposium proceedings. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare: Potters Bar.

9. Shepherdson, D., Brownback, T. and James, A. (1990). Mealworm Dispenser for Meerkats, UFA W & ZSL. Environmental Enrichment Report 2. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare: Potters Bar.

First presented at IAT Congress, Lancaster 1990

Reproduced with permission of the Institute of Animal Technology.

Published in Animal Technology (1990) Vol. 41, No.2.