Einfluß einer teilweisen Käfigtrennwand auf das Verhalten

paarweise lebender weiblicher Rhesusaffen

V. Reinhardt and A. Reinhardt

Wisconsin Regional Primary Research Center,

Madison, U. S. A.

Received June 27, 1990; accepted November 2, 1990

Key words: Rhesus monkeys, Macaca mulatta, caging, privacy, behavior

Summary

Thirty paired female rhesus monkeys were tested in a control situation when companions had no privacy, and in an experimental situation when they were offered the option to move behind a panel and be alone.

Paired partners spent significantly more time in close proximity (same half of the cage) when the privacy panel was provided (mean, with panel = 76.0 %/h vs. mean, no panel = 60.8 %/h; p < 0.005). At the same time, they were more engaged in affiliative interactions (mean, with panel = 37.4%/h vs. mean, no panel = 26.5%/h; p < 0.025) while the incidence of agonistic interactions tended to decrease (mean, with panel = 0.3/h vs. mean, no panel = 2.2/h; p < 0.1).

It was concluded that rhesus monkeys have a need for companionship. They prefer to stay in close proximity with a compatible partner even though this may reduce their available cage space. It was further concluded that companions have no need for prolonged periods of visual seclusion, but occasional privacy is beneficial for their relationship.

Introduction

There is growing consensus that laboratory primates should be housed in a social environment to facilitate the expression of species-typical features in baseline physiology and behavior (Bramblett 1989; Fouts et al. 1989; Gilbert and Wrenshall 1989; Markowitz and Line 1989; Pereira et al. 1989; Snowdon and Savage 1989; Line et al. 1990). Pending federal rules stipulate that laboratory nonhuman primates have to be provided with means to actively express their social disposition (USDA 1990).

No group formation technique for adult, previously single-caged animals has been reported for any macaque species that is safe enough to be implemented as a standard procedure. Reliably safe methods of pair-housing of previously singly caged individuals have recently been developed for rhesus macaques and long-tailed macaques as effective compromise strategy for social enrichment (Reinhardt et al. 1987; Reinhardt 1988; Line et al. 1990; Reinhardt 1990a). Pair-housing is not associated with health hazards (Reinhardt et al. 1988; Reinhardt 1989a; Reinhardt 1990b), it does not constitute a socially distressing situation (Reinhardt 1990c), and it does not jeopardize common research protocols and routine management procedures (Reinhardt et al. 1989). Skeptics, however, argue that it is impossible to know if rhesus monkeys have a real need for companionship. Paired animals have no choice but living together; perhaps, they merely tolerate each other and would actually prefer living alone.

The present paper addresses this concern. Partners of compatible pairs of rhesus monkeys were offered the choice to stay in close proximity in one half of a double cage or to be alone in different halves of the cage with visual seclusion

Methods

Thirty adult (older than 5 years) female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were the subjects of this study. The animals lived in pairs and were housed in double cages (85 cm deep, 170 cm wide, and 85 cm high). Cages were provided with two diagonally suspended PVC pipes for exercising and perching and two loose branch segments for gnawing and manipulation (Reinhardt, 1989b). Companions were compatible and had shared the same cage for I - 3 years. They had visual and auditory contact with other conspecifics of the same sex, caged in the same room. Commercial dry food was fed once a day at approximately 07:30, with a fruit supplement at approximately 15:00. Water was supplied ad libitum. Room temperature was maintained at 2 1 T, with a relative air humidity of 50 % and a 12-hr light/dark cycle. The animals were strictly undisturbed by human activities (i. e., no personnel entering the room, no handling of other animals in neighboring rooms or hallways, no flushing of drop pans) between 11:45 and 13:15. Each pair was observed during this quiet time from 12:00 to 13:00 in the following two situations:

1. Control situation: Companions were in their home cage.

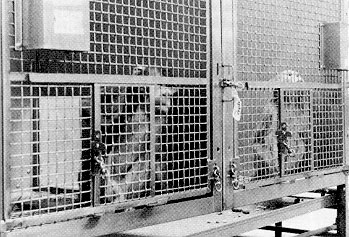

2. Experimental situation: After the control observation, a privacy panel was inserted between the two halves of the cage. This panel consisted of a sheet of stainless steel with a rectangular 23 x 32 cm passage hole close to the back wall of the cage (Fig. 1). If the two animals chose to stay behind the panel in different halves of the double cage, they no longer had visual contact with each other. Companions had been given 7 day to adjust to the panel.

Each pair was observed for 2 h (one hour during the control situation plus one hour during the experimental situation), and all 15 pairs together for a total of 30 hours. Observations were made by the first author, who sat in front of the double cages and made manual recordings. Frequency of agonistic interactions, time periods (in seconds) in which companions were engaged in affiliative interactions, and time periods (in seconds) in which they were located in the same half of the cage were recorded in the control and in the experimental situation. The PVC pipes and the loose branch segments were removed for the study period (one day before the control situation-observation until the termination of the experimental situation-observation) to eliminate their influence on the animals' location in the cage.

Statistical analysis was done with Student's paired t-test (Siegel 1956).

Results

Companions spent an average 76..0 ± 21.9 % of the time (2736/3600 s) in the same half of the cage in the experimental situation but only 60.8 ± 17.3 % of the time (2189/3600 s) in the control situation. The difference was of statistical significance (t = 3.455, p < 0.005).

The animals were engaged in affiliative interactions (grooming, huddling, rough-and-tumble play) for an average of 37.4 ± 21.3 % of the time (1346/3600 s) in the experimental situation but only 26.5 ± 18.0 % of the time (954/3600 s) in the control situation. Again, the difference was significant (t = 2.940, p < 0.025).

Partners exchanged in average 2.2 ± 3.8 agonistic interactions (yielding, fear-grinning, threatening, pushing, slapping) per hour in the control situation but only 0.3 ± 0.4 agonistic interactions (yielding, pushing) per hour in the experimental situation. The difference was not significant (t = 2.047, p < 0. 1).

Discussion

The findings of this investigation were unexpected: Paired companions did not make apparent use of the option of getting away from each other but on the contrary spent more time in close proximity when a privacy panel was provided. This underscores the social disposition of rhesus monkeys and indicates that they actually have a need for companionship. When given the choice, paired partners preferred not to be alone even though this implied a relative reduction of the available cage space.

Spending more time together did not deteriorate but rather improved the relationship of pairs. Partners spent more time interacting with each other in affiliative ways, while the incidence of agonistic conflicts tended to decrease. Apparently, the animals had no need for prolonged periods of seclusion, but occasional privacy was sufficient for them to get along even better with each other. This supports the recommendation that in any group-living situation, primates should have opportunities to move periodically into temporarily visual seclusion (Goosen et al. 1984; O'Neill 1989; Pereira et al. 1989; Poole 1987; Taff and Dolhinow 1989).

Privacy panels were implemented as part of the environmental enrichment program at the Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center for all caged rhesus monkeys living in pairs as a consequence of this investigation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. J. Wolf for providing valuable comments on this manuscript and to Mrs. M.Schatz and Mrs. Jackie Kinney for proofreading. This project was supported by NIH grant RR00167 to the Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center.

References

Bramblett, C.: Mental well-being in anthropoids. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 1-11.

Fouts, R. S., Abshire, M. L., Bodamer, M., Fouts, D. H.: Signs of enrichment: Toward the psychological well-being of chimpanzees. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 376-388.

Gildbert, S. G., Wrenshall, E.: Environmental enrichment for monkeys uses in behavioral toxicology studies. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 244-254.

Goosen, C., Van Der Gulden, W., Rozemond, H., Balner, H., Bertnes, A., Boot, R., Brinkert, J., Dienske, H., Janssen, G., Lammers, A., Timmermans, P.: Recommendations for the housing of macaque monkeys. Lab. Anim. 1984; 18: 99-102.

Line, S. W., Morgan, K. N., Markowitz, H., Roberts, J. A., Riddel, L.: Behavioral responses of female long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) to pair formation. Lab. Prim. Newsl. 1990; 29: 1 - 5.

Markowitz, H., Line, S.: Primate research models and environmental enrichment. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 203- 232.

O'Neill, P.: A room with a view for captive primates: Issues, goals, related research and strategies. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 135-160.

Pereira, M. E., Macedonia, J. M., Haring, D. M., Simons, E. L.: Maintenance of primates in captivity for research: The need for naturalistic environments. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological wellbeing of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications: 1989; 40-60.

Poole, T. B.: The UFAW handbook on the care and management of laboratory animals. New York: Churchill Livingston 1987.

Reinhardt, V., Houser, D., Eisele, S., Champoux, M.: Social enrichment of the environment with infants for singly caged adult rhesus monkeys. Zoo Biol. 1987; 6: 365-371.

- Preliminary comments on pairing unfamiliar adult male rhesus monkeys for the purpose of environmental enrichment. Lab. Prim. Newsl. 1988; 27: 1-3.

- Cowley, D., Eisele, S., Vertein, R., Houser, D.: Pairing compatible female rhesus monkeys for the purpose of cage enrichment has no negative impact on body weight. Lab. Prim. Newsl. 1988; 27: 13-15.

- Alternatives to single caging of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) used in research. Z. Versuchstierkd. 1989a; 32: 275-279.

- Evaluation of the long-term effectiveness of two environmental enrichment objects for singly caged rhesus macaques. Lab Animal 1989b; 18: 31-33.

- Houser, D., Eisele, S.: Pairing previously singly caged rhesus monkeys does not interfere with common research protocols. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1989; 39: 73-74.

- Time budget of caged rhesus monkeys exposed to a companion, a PVC perch, and a piece of wood for an extended time. Am. J. Primat. 1990a; 20: 51-56.

- Social enrichment for laboratory primates: a critical review. Lab. Prim. Newsl. 1990c; 29: 7-11.

- Living continuously with a compatible companion is not a distressing experience for rhesus monkeys. Lab. Prim. Newsl. 1990c; 29: 1-2.

Siegel, S.: Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. New York: McGRAW-HILL 1956.

Snowdon, C. T., Savage, A.: Psychological well-being of captive primates: General considerations and examples from callitrichids. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 75-88.

Taff, M. A., Dolhinow, P.: Langur monkeys (Presbytis entellus) in captivity. In: Segal, E. F., ed.: Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications 1989; 291-304.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Animal Welfare; Standards; Proposed Rules. Fed. Regist. 1990; 55: 33521- 33531.

This article originally appeared in the Journal of Experimental Animal Science 34, 55-58, 1991.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher.