By Linda Brent

The 1985 amendment to the Animal Welfare Act requires research facilities to promote the "psychological well-being" of nonhuman primates. After much debate, the US Department of Agriculture published its final ruling concerning this topic in 1991. The USDA' s new regulations emphasize social housing and other environmental enrichment procedures, such as perches and toys. Now, several years after implementation of the regulations, it is reasonable to ask if the living conditions of laboratory primates have improved. At the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research (SFBR) in San Antonio, Texas, the answer would be "yes." A once unknown term to our animal care staff, "environmental enrichment" is now part of our standard operating procedures.

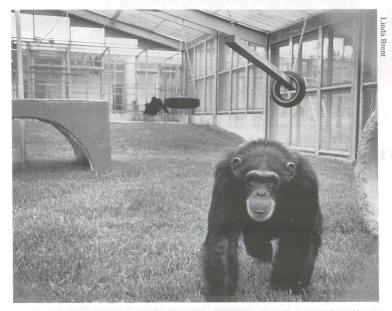

A formal enrichment program at SFBR began in 1987 in the chimpanzee breeding and research area, now holding over 240 chimpanzees. Over the years, the program has grown to encompass most aspects of the chimpanzees' lives, including housing, management, breeding, rearing and feeding. Environmental improvements include construction of large indoor cages that allow pairing of experimental animals, a grass-covered "playground" for breeding chimpanzee groups, and indoor/outdoor group housing for "retired" experimental animals. In addition, we provide toys, perches, mirrors, and foraging devices, and televisions for chimpanzees housed indoors. Management changes include leaving infants with their mothers for at least 2 years after birth and removing mothers from the breeding program who have proven to be inadequate or abusive toward their infants. Nursery areas have been greatly improved to provide important stimulation for the developing infants. Rockers, jungle gyms, numerous toys and stuffed animals, a fish aquarium for viewing, and a window to the adult chimpanzee groups nearby are examples of the enrichments available. Dedicated volunteers also spend time holding and playing with the infants.

We used the success of the chimpanzee enrichment program to guide our more recent efforts for monkeys. With over 3000 baboons and 150 other small monkeys at the SFBR, enrichment can be an overwhelming task. Luckily, the majority of monkeys are housed in large outdoor group cages or corrals that offer important opportunities for socialization and space for locomotion. To increase use of vertical space and provide shade and hiding places, we constructed a number of climbing and perching devices in the group-housing areas. We hang fifty-five gallon plastic drums as swings from suspended horizontal ladders in the outdoor cages, and we added large climbing structures similar to jungle gyms made of wood, metal, chain and wire to the corrals.

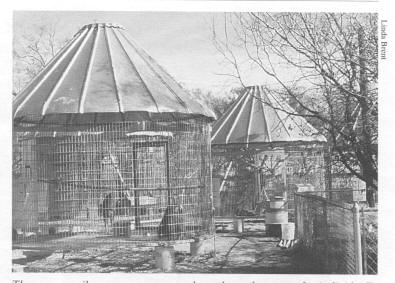

We provide individually housed animals with a variety of toys, either loose within the cage or hanging from a chain on the outside of the cage. Durable dog toys, such as plastic bones, seem to work best with the baboons and other monkeys. We provide radios as auditory enrichment for animals housed indoors. We also attempt to pair individually housed primates, and provide a large activity cage several days per month for some of the baboons. Recently constructed "corn crib" housing allows us to move individually housed baboons to small outdoor groups.

We instituted several new policies regarding the well-being of baboon infants, including providing surrogate mothers made of rolled up towels suspended from the side of the cage, offering manipulable toys, and providing regular group play periods for the infants before they are integrated into pairs. It is hoped that these procedures will more closely resemble rearing with the mother, and that some of the possible detrimental behavioral effects of nursery rearing will be lessened.

To offset the high cost of maintaining an enrichment program at a large laboratory, we make use of available items, such as the large plastic drums and shredded paper for nesting material. In addition, we post signs requesting donations from the staff, such as baby toys, empty plastic containers, and old radios or televisions. The SFBR also has a very successful enrichment volunteer program. Our volunteers assist us in filling feeding devices, giving grain to group housed baboons, playing with infant chimpanzees, and helping with paper-work. We train the volunteers to work safely with primates, and provide them with literature on primate behavior and enrichment.

Perhaps the most important and far-reaching efforts to improve the lives of the nonhuman primates at the SFBR have been in educating and training our staff. We arranged films on primate behavior and invited individuals to speak on enrichment and the behavior of wild and captive primates. We also started staff training for our Behavioral Intervention Program. The goal of the program is to provide more responsive care on an individual basis. Identifying abnormal behavior is best done by the care giving staff who are trained in the identification of abnormal behavior in primates and have daily contact with the animals.

The environmental enrichment program at the SFBR has grown tremendously in the past few years and has had many successes in addressing the behavioral needs of the nonhuman primates in our care. However, improving the environment and well-being of nonhuman primates is not achieved by reaching some static level, but rather is an evolving process in which the physical and the psychological needs of the animals are addressed on a daily basis.

Linda Brent is a Research Associate in the Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine of the SFBR in San Antonio, Texas.

AWI Quarterly, Winter 1995, Vol. 44 (1), p. 14-15.