Doug Cowley, Russell Vertein, Harry Pape, Viktor Reinhardt

Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center

University of Wisconsin

1223 Capitol Court, Madison, WI 53715, USA

Public awareness has created favorable conditions for the gradual improvement of conventional housing conditions of laboratory macaques.[1-3] What about the human primates who care for those animals? Animal holding facilities are usually designed by architects - with too little input by animal care professionals - to accommodate a maximum number of animals; possible health implications for those responsible for the care of the animals are often overlooked. The present paper deals with a typical example.

Cages for macaques are usually arranged in upper and lower rows, facing each other. Research protocols as well as routine management procedures require the transfer of conscious animals on a regular basis. Individual adult macaques may weigh well over 10 kg, the box in which they are transferred weighs approximately 6 kg. The transfer typically involves the following steps:

1. Positioning the transport box at the front of the cage.

2. Catching the animal by opening the doors of the box and the cage.

3. Carrying the transfer box out of the animal room.

4. Releasing the animal into a different cage (e.g., breeding) or placing the box on the floor (e.g., animal waits while its cage is sanitized) or lifting it on a restraint apparatus (e.g., animal is treated, blood is collected) or on a scale (regular body weight control).

5. Returning the animal to its homecage.

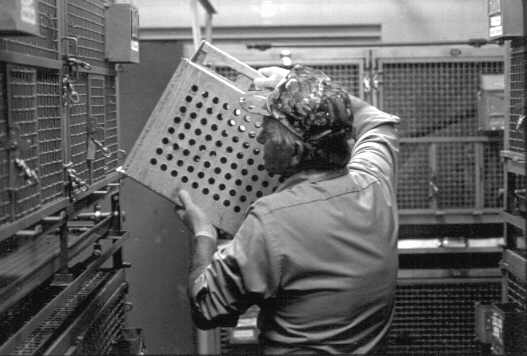

Transferring adult macaques on a daily basis constitutes a repetitive strain on the caretaker's back, especially on days when large numbers of animals are scheduled to be moved, e.g., cage sanitation, weighing, husbandry-related blood screening. The strain is particularly severe when upper-row caged animals are moved. In those cases, the transport box with the animal must be carefully lowered from a height of approximately 150 cm to the floor. The reverse maneuver must be performed when the animal is returned (Figure 1).

The authors of this paper have developed recurrent back problems associated with severe pain as a result of transferring adult rhesus and stumptailed macaques on a daily basis. They have taken the following initiatives to ameliorate this health hazard:

1. Animals in transport boxes are no longer carried by hand but moved on push-carts.

2. Animals are no longer kept in transport boxes while their home cages are sanitized, instead they are temporarily housed in the cage across the aisle. This is accomplished in the following way:

a) The animals living in the cage opposite those to be transferred are confined to one half of their double cage by inserting a cage divider.

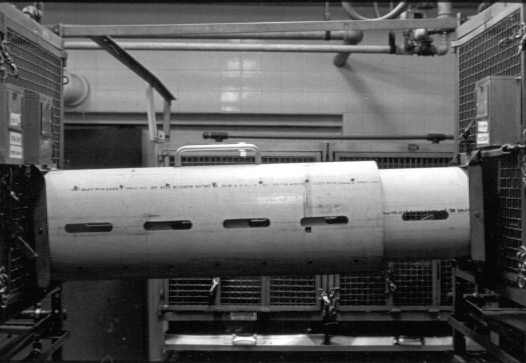

b) The animals of the cage to be sanitized enter the empty half of the opposite cage via a transfer chute (Figure 2). The chute is moved on a push-cart with a platform that is adjustable to the level of lower-row and upper-row cages.

c) The chute consists of two PVC pipes of varied sizes. The one with the smaller diameter is inserted into the one with the larger diameter, allowing easy adjustment to the distance between the opposite cages. The two entrances of the chute are mounted on rectangular stainless steel frames that are coupled with the open cage by positioning them on two supporting hooks in front of the cage door (Figure 2).

d) The transfer is reversed after completion of the cage sanitation.

3. The animals are no longer removed from their homecages for blood collection, instead they are trained to actively present a leg or the inguinal area for venipuncture [4] (Figure 3).

4. The animals are no longer removed from their homecages for routine intramuscular injections (e.g., diabetes mellitus treatment with insulin) and routine topical applications of experimental drugs (e.g., baldness study requiring "painting" of forehead with test liquids), instead they are trained to cooperate during these procedures in their familiar cages [5] (Figure 4).

The four changes in animal transfer techniques offer a partial solution to back problems. Animals must be removed from their cages for weighing and TB testing, medical examinations and treatments, temporary transfer to breeding partners, permanent transfer to different housing areas. Back strain resulting from lifting animals in transport boxes is unavoidable on these occasions. Housing macaques in a single row at approximately even level with push-carts would be a more satisfactory solution to the problem. A work environment of this type would minimize the risk for the animal care personnel of developing back problems because undue lifting would no longer be necessary during daily transfers of animals.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dick Pape and Duane Zweifel for their technical assistance and to Bob Dodsworth for preparing the photographs. Supported by NIH grant RR-00167 to the Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center .

References

1. Segal, E.F. (ed.) (1989). Housing, Care and Psychological Well-being of Captive and Laboratory Primates. Noyes Publications, Park Ridge.

2. Novak, M.A. and Petto, A.J. (eds.) (1991). Through the Looking Glass. Issues of Psychological Well-being in Captive Nonhuman Primates. American Psychological Association, Washington.

3. U.S. Department of Agriculture (1991). Animal Welfare, Standards, Final Rule. Federal Register, 56: 6499-6500.

4. Reinhardt, V. (1991). Training adult male rhesus monkeys to actively cooperate during in-homecage venipuncture. Animal Technology, 42: 11-17.

5. Reinhardt, V. and Cowley, D. (1990). Training stumptailed monkeys to cooperate during in-homecage treatment. Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 29(4):10-11.

Reproduced with permission of the Institute of Animal Technology.