Wallace W. Swett

Author presents case histories of Primarily Primate's treatment of individual primates with problems common to humanized and abused primates. Among the methods effectively used were gradual introduction to other primates, (sometimes with the use of portable cages), surrogate mothers, territorial manipulations, and use of the knowledge of different species' social structures. Particular methods of rehabilitation must be decided on a case-by-case basis. Education of the general public and legislation are seen as major ways to control humanization and abuse of primates. Keeping primates in captivity is seen as nearly always leading to deprivation.

Key Word Index

monkeys, animal welfare, husbandry, animals

The Humanized Primate

When we talk about a humanized primate, we mean one who has been reared strictly in human captivity, away from conspecifics. Because these animals have been around humans for most of their lives, their nature resembles that of the people who raised them more than they reflect their own animal nature. The more intelligent the primate is, the more he or she is a candidate for neurosis. As he or she is out of his or her natural element, the animal lives a twilight existence, not knowing the proper signs, smells or greetings of his or her own kind.

A Primate's Journey from the Wild to Captivity

Most primates are imported into this country when they are infants, and sold to dealers and individuals for profit. Life prior to arrival in North America is usually one trauma after another. For example, the most common way for poachers to obtain infants is through the slaughter of entire primate troupes or shooting the mothers. Many of these babies are plucked from the bodies of mothers who had tried to protect their young. From there, the young are often subjected to weeks of holding and travel in cages. They often receive poor food, little water, and close confinement before ending up in the United States as yet one more victim of the exotic pet trade.

ven when primates end up in a human household, life away from their natural surroundings, including social settings, is bound to be deprived. When primates are young, they are biddable and cute. As they grow older, they tend to revert to their natural wild instincts. Any wild animal behaving in his or her natural ways can be frightening to a human being, and it is only natural that humans try to take steps to contain the "wildness." Tooth extraction is a common method of disarming a primate. Beating, starvation, electric shock, and imprisonment are additional ways that have been used to control adult primates.

Another problem is malnourished individuals. We have found that primates are oftentimes unintentionally being nutritionally deprived. For example, Sammy, a South American woolly monkey (Lagothrix lagothricha), came to us sickly and malnourished, his bones fused together. Instead of being given a proper diet, he was fed sugary breakfast cereals and sweet fruit by his human handlers, who kept Sammy as a "pet." When he arrived here, he was unable to climb and romp like a normal primate. Instead, he shuffled around on his wrists.

Eventually the stress of captivity shows on primates. Excessive grooming, aggressive behavior, self-mutilation, and terrible phobias are common in the primates that arrive at our sanctuary.

Perhaps the greatest crime of all is depriving primates of relationships with their own kind. Then they never learn the signals, greetings and social structure that make animals so uniquely a part of their troupe.

From these experiences, we have come to the conclusion that a primate does not belong in human captivity. Even under the best of circumstances, both primate and human end up ultimately as losers.

Methods of Rehabilitation

In 1978, when we first began to rehabilitate abused primates, the concept of healing these sad animals was considered impossible by most people. When we approached specialists and zoos for advice, we were told the same thing: a primate reared in captivity was doomed to a painful half-existence. The only release from suffering was said to be euthanasia.

Many came to us after isolation and torture. They had been deprived of their fellows, of play, of climbing. Some had become psychotic, no longer responsive to their environment.

From the start, however, we always felt there was an alternative to death. Through reading and discussions with some especially caring and sensitive primate experts, they confirmed our belief that rehabilitation was possible through hard work and training. As there are many different species of primates, and as many individual differences within a species, we learned that there was no single best method for rehabilitation.

Whenever we are confronted with an abused, humanized primate who needs to be reintroduced to his or her own kind, we use methods unique to the individual as well as species-specific conditions and do a study of all the specifics in the situation.

The only things we keep in common, from case to case, are learning the troupe behavior of a species of primate in the wild, knowing what the particular individual's past was, and keeping human interference during rehabilitation to an absolute minimum. Beyond these factors our methods are as varied as the species of primates and individual personalities in existence.

Territorial Introductions

Because primates are territorial beings, simply placing a newcomer into a primate group to fend for him or herself will not work. The group in residence can literally attack or kill an "outsider." To lessen the territoriality with adult primates, we try various methods. One of our methods is to remove the group to another enclosure, allow the newcomer to enter the old space, and then slowly reintroduce the group. In another method, we place the newcomer in a new enclosure, then introduce the group to the newcomer in that new enclosure. Still another method involves having each member of the group spend time with the newcomer, after which we introduce the individual to everyone at once. These methods are oftentimes able to diffuse territorial aggressions.

Familiarity with the troupe structure is of great assistance. For instance, knowing that the patas monkey (Erythrocelous Patas) group contains only one dominant male in the wild means that we will not try to introduce more than one adult male patas monkey into a troupe at Primarily Primates.

Portable Cages

Many primates who come to us have been locked up all their lives in solitary confinement, and have never been outdoors. They are easily frightened by anything dealing with nature, let alone another primate. In situations such as these, portable cages are a boon to our work. In these cages, primates can be moved outdoors to a new enclosure or next to another primate for minutes at a time until the newcomer is able to adapt. The length of time necessary in this cage depends on the stresses the primate has endured and his or her reaction to the new situation.

Tyrone, an abused male chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) who came to us from a terrible roadside zoo, was successfully rehabilitated with other chimps through the portable cage method. After he had been here six months, Tyrone's cage was attached to the Chimp Complex, where a group of chimpanzees reside, through the use of a special walkway. Tyrone was able to observe this arena of chimpanzees at play, fighting, and offering security to each other from the safety of his cage. In time, Tyrone picked up the traits and signals, and was eventually successfully introduced into the colony of chimpanzees.

Introduction to Different Primate Species

At Primarily Primates, we do not have the luxury of massive numbers of species to which we can introduce a bewildered newcomer. Because primates come to us according to need, we could end up with a troupe of spider monkeys but only one macaque. This is where troupe knowledge comes in handy. By placing similar—or more adaptable—species of primates together, rehabilitation becomes more effective. For example, macaques (Macaca) and baboons (Papio) tend to adapt very well together. By the same token, woolly logothrix and spider monkeys (Ateles) have similar troupe structures, and thus can get along with more ease than can vervets (Ceropithecus Aethiops) and macaques.

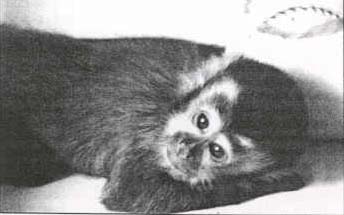

Mickey, a baby hybrid capuchin monkey, was totally humanized, abused, and confused when he first arrived here. Having been passed from human to human, Mickey came here as a tiny, frail and insecure morsel of a personality. Mickey was placed with Tootsie Roll, a boisterous, playful, outgoing baby female tufted capuchin (Cebus apella). At first, the frightened Mickey spent his days curled up in a corner, while Tootsie Roll climbed about, trying not to touch him. Soon, Tootsie Roll began to initiate play with him by poking him and wrapping her tail loosely around him. Eventually, as Mickey lost his fear and apathy, he began to bond with his female companion. The two started spending most of their time together, either playing or sleeping curled up with each other. In time, Mickey developed more species-specific social behaviors, and was eventually introduced to a bachelor group.

Tootsie Roll, a tufted capuchin

Mickey, a hybrid capuchin monkey

Foster Mothering

Young primates are easier to rehabilitate, not having been under the influence of humans for as long as their adult counterparts. It seems to make them more adaptable. The important thing we try to provide for these young individuals is a foster mother. We have many gentle mothers in our population who are ideal for this purpose. Some of them are "true mothers," grooming and taking charge of the little ones as though they were their own. Others couldn't care less about the mothering instinct, but do not mind if the baby clings to them. The important thing is for the babies to have a mother figure who will carry them, be a role model, and give 24-hour companionship that a human just cannot provide.

When Tootsie Roll was ready, she was successfully fostered to Mandy, an adult female tufted capuchin. The two now reside in a colony of other female capuchins. The colony includes an ex-pet, an ex-laboratory animal, and, ironically, Tootsie Roll's natural mother. Although the mother ignores her daughter, the other two females have become "aunts" to Tootsie Roll. It is common to see a capuchin carrying her young "niece" when she is afraid or needs comfort.

In order to allow the babies more potential to learn and grow with their own species, we keep the baby fed without human interference. For this purpose, we use a surrogate mother, which is a rolled up artificial sheepskin. While the baby clings to the surrogate, we try various methods to give the baby a bottle. Sometimes it is held through the bars of a cage. Other times, it is placed in a special bottle holder.

One of our successful cases was a baby vervet monkey. Not having other vervets on the grounds at the time, we introduced the baby to the sheepskin mother and a bottle. After much patient work, the vervet accepted both. When he grew older, we introduced him to a mother squirrel monkey because both species have somewhat similar group structures. The squirrel monkey adopted the vervet as her son. Today the vervet is a totally rehabilitated primate who lives with other vervets. After his arrival to adulthood, another adult vervet, this one a female, came to us. The male was an especially good influence on the female during the course of her rehabilitation because he was able to teach her monkey behaviors, partly because he had been raised with monkeys instead of humans.

There is only so much we can do, however. We can introduce newcomers to other primates, keep them fed, and offer medical attention when needed. It is ultimately up to the primates to rehabilitate. They must learn to communicate among themselves, maintain and recognize the signals, and learn to live together in harmony. Some succeed in this. We have grouped a large colony of bachelor chimps, who live together with little animosity. We have also created a group of squirrel monkeys who have adapted well to each other after years of isolation.

Socialization and rehabilitation can take from three months to three years and beyond. Sometimes, however, a primate is found who is beyond hope. This unfortunate individual has usually been abused or humanized for too long. Although we will provide a home with us for the rest of his or her life, the individual is unable to learn species-specific behavior.

Introducing Primates Back Into the Wild

Often we are asked if we will ever introduce our charges back into the wild. This is probably what every wildlife rehabilitation worker hopes for, and we are certainly no exception. While we have several good candidates for reintroduction, it takes more than an adaptable primate and willing helpers. An appropriate wild area is also needed. We are currently looking for available protected wilderness and working on the administrative details for our first reintroduction effort. By the end of the decade, we hope to start releasing some of our primates back to their natural habitats.

Preventing Abuse Before it Occurs

The best method of preventing humanization and abuse is to stop primates from falling into human hands. The preferred place for wild animals is in the wild. As simple as this sounds, it is the heart of the matter, and it is very difficult to enforce.

If the public is as convinced as we are that it is unfair to deprive a living creature of its natural habitat, whether the creature be a human being or a woolly monkey, then this kind of exploitation will be reduced. At this time, certain countries have laws against primate importation. Sadly, these laws are difficult to enforce. With stronger legislation from our government against importation, poachers and importers may find it more difficult and expensive to hunt and sell primates. Primarily Primates supports efforts to ban importation.

Education goes hand-in-hand with legislation. As the public knows more about unintentional problems for captive primates, people are more likely to contact Congress about further enforcement of bills banning exotic animal importation.

At Primarily Primates, we try to give primates the opportunity to experience their natural background and behaviors. On the day that we can rest assured that these glorious creatures can remain in the wild, we will close our doors. Until that time, however, we are here to give those primates a chance to live a more natural, satisfying life.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Wally has asked that we make it clear that the methods described in this article are not given in full detail. Many factors must be considered by very experienced personnel before attempting resocialization, or the animals can be traumatized, injured, or killed.

Reproduced with permission of the editor. Published in Humane Innovations and Alternatives Vol. 7, 440-443, 1993.

Photographs were scanned from a photocopy. Two of them could not be reproduced (too dark).