In today’s specialized food system, the majority of animals raised for food are transported to different locations based on their “stage of production” such as breeding or fattening. At minimum, animals are transported from the farm to the slaughterhouse, and many will be subjected to the additional stress of a livestock auction.

Transport is recognized as one of the most stressful times in a farmed animal’s life. In addition to the vibration, noise, fumes, and unfamiliar environments, transported animals often experience prolonged food and water deprivation, intense crowding, exposure to extreme heat and cold, and physical stress and injuries from loading and having to balance in a moving truck. The risk of injury is particularly high during loading and unloading, when electrical prodding and other brutal handling methods are often used to move fearful and disoriented animals. Trucks waiting in line to unload is a serious problem as well; animals in trucks that are stalled in queues or stuck in traffic, especially on asphalt in hot weather, are extremely stressed and may even die as a result.

Transport is difficult even when the animals are healthy and physically fit, but the stressors are amplified for young, weak, diseased, or injured animals. The young and those already in a state of poor welfare are less able to cope with the challenges associated with transport and often experience further deterioration in condition. Particularly vulnerable animals, such as “cull” animals and neonatal “surplus” calves have less economic value than their “market” counterparts—thus, their welfare during transport is even less of a priority to producers and carriers.

The consolidation of the meat industry over the past few decades has resulted in fewer slaughterhouses, forcing animals to endure longer drives. In 1873, when most farmed animals traveled by rail, the Twenty-Eight Hour Law was created to ensure that animals traveling 28 hours or more were allowed to rest for at least five hours, as well as have access to food and water. In 2006, the US Department of Agriculture, charged with administering the law, announced it was applying the law to trucks. However, through public records requests, AWI has discovered that the law is poorly enforced. There is little meaningful protection for farmed animals during transport.

A similar consolidation in the dairy industry has led to the practice of routinely subjecting hundreds of thousands of young, unweaned calves to stressful journeys of up to 1,000 miles or more throughout the country.

International Transport

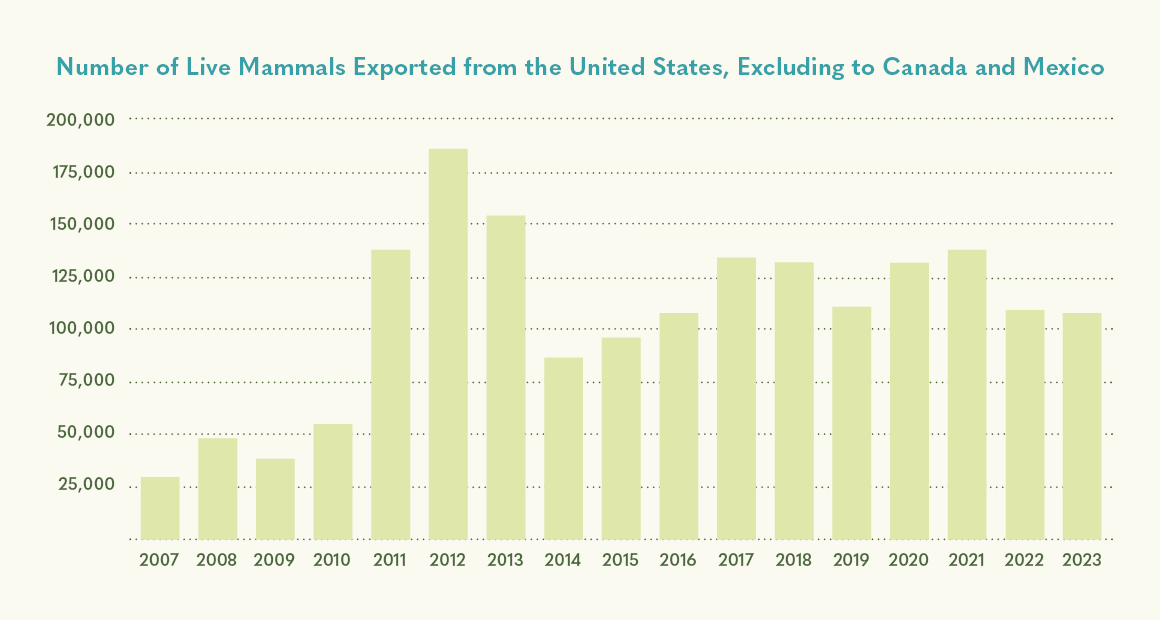

International transport of farmed animals from the United States has increased significantly. Large numbers of animals—many of them pregnant dairy cattle—were transported from the United States beginning in 2010 to establish breeding herds in Turkey, Russia, and Kazakhstan. Exports of live animals increased steadily through 2012, when nearly 200,000 live animals were exported from the United States to countries other than Canada or Mexico. The number of animals exported has leveled off somewhat in recent years, but still remains higher than historical averages prior to 2010.

While most exported animals are flown to their destination, some (mainly cattle) are subjected to ocean journeys that can last weeks. Most of the over 503,000 cattle exported to countries other than Canada and Mexico since 2005 were shipped by sea—primarily to Russia and Turkey. During transport, many stressful experiences—including inadequate ventilation, loud noises, motion sickness, and heat stress—severely impact animal welfare and make the animals more susceptible to illness and disease.

In August 2012, more than 1,000 breeding dairy cattle shipped to Russia from Galveston, Texas, died during the voyage or shortly after arrival. Another 200 animals, too ill to be offloaded, were never accounted for and are feared to have been dumped at sea. The deaths have been attributed to a breakdown in manure removal and ventilation systems, causing the animals to suffocate on ammonia fumes.

In December 2013 and January 2014, more than one dozen carcasses of US cattle washed ashore in Denmark and Sweden. European law enforcement authorities investigating the incident concluded that the dead cows had been dumped in the Baltic Sea after dying during a voyage from the United States to a port in Europe.

AWI recommends that no animals be transported such long distances and for such long periods. If they are, however, it is critical that only fit animals make the journey. To ensure that only healthy and fit animals are subjected to the rigors of international transport, in February 2011 AWI petitioned the USDA to adopt “fitness to travel” requirements for all farmed animals exported to any foreign country except those traveling overland to Canada or Mexico. AWI recommended that the USDA employ the fitness requirements included in the animal transport standards of the World Organisation for Animal Health (a.k.a. “OIE,” its initials in French).

In September 2013, the USDA officially responded to the petition, indicating that it would amend its current regulations “to better ensure the welfare and safety of animals during transport for export to foreign countries.” Proposed changes to the regulations were published in February 2015 and finalized in January 2016. They include fitness to travel criteria and a requirement that any deaths be reported within five days of the completion of an international journey.

Auctions and Markets

Auctions, also commonly referred to as “stockyards” or “livestock markets,” are establishments where farmed animals are kept until they are sold or shipped to another destination. Some animals may have to endure transport to multiple auctions before they are ultimately sold for fattening, or more likely, for slaughter.

In the United States, auctions are regulated by the Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA), a USDA agency that promotes the marketing and trade of farmed animals and agricultural products. Historically, GIPSA has refused to address animal welfare concerns, and incidents of abuse and neglect occur with no repercussions for those responsible.

Auctions have a poor record of animal welfare. There exist no standard protocols for providing animals with sufficient food, water, space for rest, shade in hot weather, and comfortable quarters in cold weather. Animals too sick or injured to walk (referred to as “nonambulatory animals” or “downers”) may be unable to reach food or water and can suffer from inhumane attempts to force them to move, including being rammed with forklifts, shocked repeatedly by electrical prods, and dragged by chains around their necks or legs. Downed animals may be left to die, and sometimes even tossed onto garbage piles while still alive.

Due to serious welfare concerns and the potential for spreading disease, AWI opposes the selling of animals at livestock markets.