Confinement

The rearing of farmed animals today is dominated by industrialized facilities known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs (often referred to as “factory farms”) that maximize profits by treating animals not as sentient creatures, but as production units. Raised by the thousands at a single location, animals are confined in such tight quarters that they can barely move, let alone behave normally.

- Four or more egg-laying hens are packed into a battery cage, a wire enclosure so small that none can spread her wings. Being held in such close confines, the hens peck at each other’s feathers and bodies.

- Pregnant sows spend each of their pregnancies confined to a gestation crate—a metal enclosure that is scarcely wider and longer than the sow herself. Unable to even turn around, sows develop abnormal behaviors, and suffer leg problems, bladder infections, and skin lesions.

- Growing pigs are confined to slatted, bare, concrete floors. Stressed by crowding and boredom, they frequently resort to biting and inflicting wounds upon their penmates.

- In factory dairies, cows spend their entire lives confined to concrete. To boost production, some cows are injected with the growth hormone rBGH or rBST, which increases a cow’s likelihood of developing lameness and mastitis, a painful infection of the udder.

Painful Physical Alterations

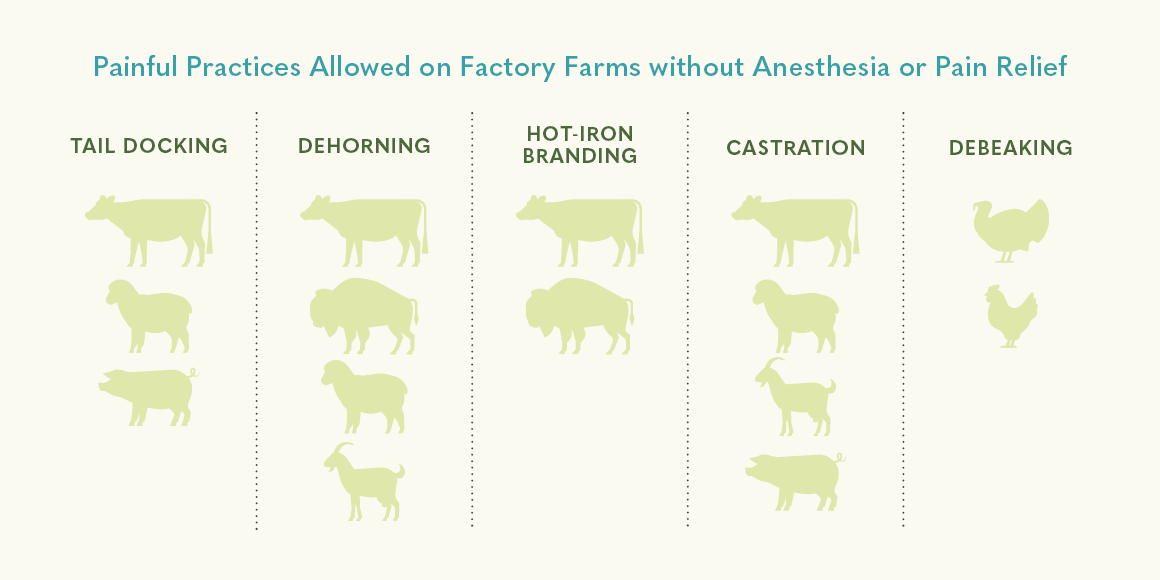

In order to facilitate confinement of these animals in such stressful, crowded, unsanitary conditions, painful mutilations such as cutting off the horns of cattle, cutting off the beaks of chickens, and docking the tails of sheep, pigs, and indoor feedlot cattle are routinely performed. Pain relief is rarely provided.

Cattle and goats, if not naturally hornless, typically undergo procedures to stop horn growth at a young age. In very young animals, when horns have not yet formed, disbudding is performed by removing horn-producing tissue via burning (hot iron) or chemical means (caustic paste). Once horn-producing tissue has attached to the skull, various physical means are used to dehorn, which may involve cutting bone and entering the frontal sinus of the skull. Disbudding is preferred over dehorning because it carries a lower risk of complications and is significantly less invasive and painful; however, recent research shows that even disbudding causes pain for weeks to months after the procedure.

Cattle and goats are disbudded or dehorned to reduce the incidence of carcass bruising caused by horn injuries during transport, as well as to reduce the risk of on-farm injuries to other animals and people. Rather than employing routine dehorning or disbudding, some producers raise hornless (polled) animals.

Unless used for breeding, most ruminants (cows, goats, sheep) and pigs in production are castrated. Methods of castration vary between species and include surgical removal of the testicles with a scalpel or knife, application of a tight rubber band to cut off testicular blood supply, or the crushing of testicular blood vessels. When deprived of blood, the testicles eventually die and slough off after several weeks. All of these methods cause pain. Surgical castration and crushing are more painful at the time of the procedure, while pain due to banding increases in the hours and days after the procedure and persists longer. With all methods, it is common for pain to last for days to weeks.

Reasons for castration—which vary from species to species—include reducing aggressiveness, preventing unwanted breeding, and modifying carcass characteristics or meat quality. For pigs, the primary reason for castration is to avoid an undesirable odor and flavor in pork from sexually mature boars.

Historically, tail docking has been performed on pigs, sheep, dairy cattle, and cattle reared on feedlots with slatted floors. It is being phased out in the US dairy industry.

In cattle and sheep, most producers use a rubber band to cut off circulation to the bottom two-thirds or more of the tail, causing the tissue to gradually die over three to seven weeks from lack of blood supply. Eventually, the necrotic tail tip falls off or is cut off. Other methods include cauterizing with hot irons or surgical amputation. In piglets, blunt trauma, scissors, sharp instruments, or hot cautery are most often used to remove most of the tail.

The motives for tail docking vary with species and production type. Cattle raised for beef in indoor feedlots with slatted floors may have their tails docked because producers believe it will reduce the tail tip injuries (and subsequent infections) caused by being stepped on by other cattle. Tail docking was once routinely performed on dairy cattle to promote hygiene during milking; however, research has shown no benefit from docking the tails of dairy cows. For this reason, both the American Veterinary Medical Association and the National Milk Producers Federation oppose routine tail docking. California, Rhode Island, and Ohio have statutes or regulations outlawing routine tail docking.

Sheep’s tails are docked to reduce the incidence of fly strike, an infestation of fly larvae in the skin due to accumulation of fecal material.

In pigs, tail docking is typically carried out within the first week of life, often in conjunction with other “piglet processing” procedures, such as castration, teeth clipping, and ear notching. The primary reason producers dock pigs’ tails is to prevent tail biting and chewing by penmates. While incidents of tail biting often occur in unpredictable outbreaks, it is associated with certain management factors, including insufficient access to substrates for rooting and foraging, overcrowding, nutritional and feeding practices, and genetics. Tail docking reduces the risk and severity of tail biting but doesn’t eliminate it.

Tail docking has long been recognized as causing acute pain, but there is increasing evidence that it may also cause chronic pain through the formation of neuromas (the disorganized growth of nerve cells at the site of a nerve injury).

Beak trimming, also known as de-beaking or partial beak amputation, is performed nearly universally on chickens raised for egg production (laying hens), chickens kept as breeders to produce birds who will be raised for meat (broiler breeders), turkeys, and some other fowl. The procedure involves using a hot blade to cut off part of the beak or using high intensity infrared light to damage beak tissue, causing it to die and slough off. Typically, one-third to two-thirds of the beak is removed. Several factors can affect the severity and duration of acute and chronic pain associated with beak trimming, but generally, the hot blade method is considered more painful than the infrared method.

Beak trimming is performed primarily to decrease pecking of feathers, vents, wattles, and combs and to prevent cannibalism. It is also performed to improve feed efficiency by decreasing feed waste, as the birds are less able to manipulate feed and throw it out of the feeder. Chickens raised for meat (broilers) typically do not have their beaks trimmed because they are slaughtered at such a young age (4 to 7 weeks) that they don’t develop the pecking behavior that the practice is intended to mitigate.

Turkeys and broiler breeders often have the claws of the three forward-facing toes on each foot removed or reduced. Today, this is achieved primarily by exposing the toes of day-old chicks to microwave energy via a claw processor machine, killing the tissue and causing it to fall off within a few weeks; however, some producers use hot blades or surgical scissors to remove the tip of toes. This is performed to decrease risk of carcass bruising and scratches.

Pigs are born with eight fully erupted sharp teeth—often called needle teeth. Piglets use their needle teeth to establish “teat order” during the first 24 hours of life, and to defend “their” teat from siblings. Due to a concern that these teeth can injure the sow’s udders or other piglets, some producers clip or grind these teeth as part of the “piglet processing” (described above) during the first week of the piglet’s life. Both clipping and grinding often expose the nerve-filled pulp cavity of the tooth, causing acute and long-term pain. Producers increasingly select for large litter sizes, which increases the risk of needle teeth–associated injuries to the mother pig’s udders and to other piglets.

Branding is performed to identify cattle and is primarily used by the beef industry. Both hot-iron and freeze branding cause prolonged pain, but hot-iron branding causes second- and third-degree burns and is recognized as being more painful. Branding pain lasts for weeks to months.

Ears are notched or pierced for tagging in ruminants and pigs as a form of identification. Ear tagging involves using a tag applicator to pierce the ear tissue between two cartilaginous ridges, while ear notching involves cutting one or more wedges out of ear tissue into a particular pattern.

Pain Relief for Physical Alterations

With the exception of chickens raised for meat, the vast majority of farmed animals in the United States undergo at least one painful physical alteration over the course of their lives. Physical alterations cause significant pain during and after the procedure, and many cause chronic pain that may persist until the animal is slaughtered. Farmed animals may also experience chronic pain due to production diseases—ailments that arise from the husbandry conditions inherent in intensive animal agriculture and become more prevalent or severe as the intensity of production increases. Lameness and mastitis are examples of production diseases.

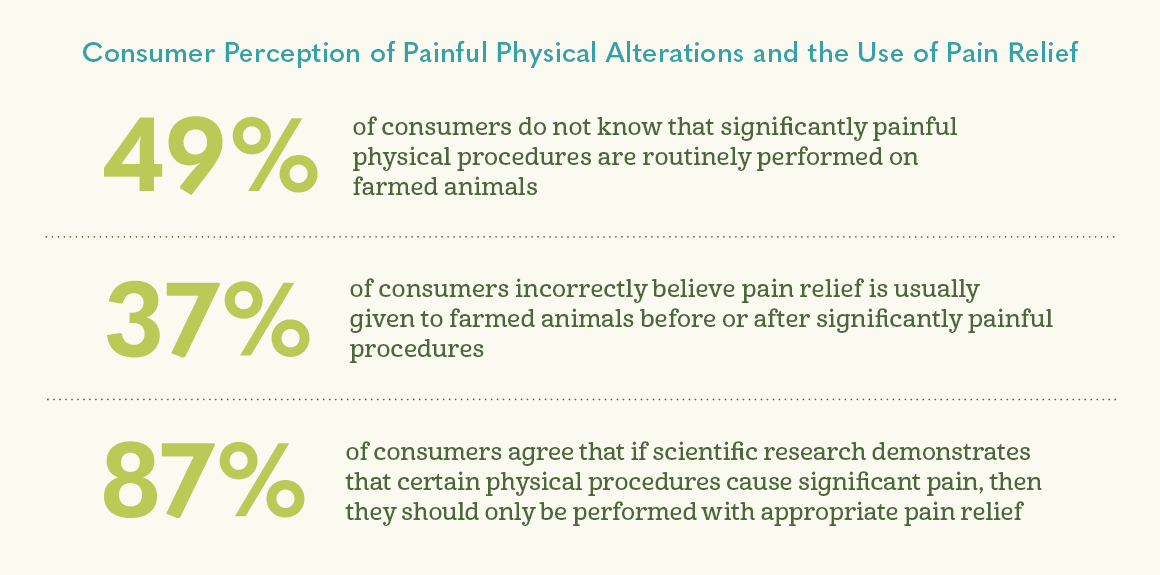

Despite the ubiquity of painful procedures and conditions, it is rare for farmed animals to receive adequate pain relief. In fact, with the exception of dairy cattle, most farmed animals receive no pain relief at all for procedures.

There are several reasons for the lack of adequate pain management in farmed animals. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stricter requirements for use of drugs in “food-producing” species, primarily to ensure no drug residues remain in marketed meat, milk, or eggs. Currently, there are no FDA-approved drugs specifically labeled for relief of pain from painful procedures in these species. While there are pain medications recognized as being effective for such animals, they must be used in an “extralabel” fashion—i.e., in a manner that deviates from the FDA-approved label, and this requires veterinary oversight. Some veterinarians are reluctant to shoulder the additional record-keeping and liability associated with extralabel drug administration to farmed animals. In addition, nearly all on-farm procedures are conducted by producers—not veterinarians—and not all producers have the “veterinary client patient relationship” required under federal law for a veterinarian to prescribe or administer pain-relieving medications in an extralabel manner.

There are also logistical and financial challenges to providing adequate pain management to large populations of farmed animals in commercial settings. For example, after administration, pain medications require time to take effect. This may mean handling animals more than once and can prolong the amount of time needed for processing. Furthermore, many physical alterations result in long-term pain, which would require repeated administration of medication to address, thus increasing drug and labor costs. While adequate pain management may improve some metrics important to producers—such as weight gain and disease resistance—it also adds to the cost of production.

The consolidation of animal agriculture industries means that for pain management to become routine, buy-in is needed from the multinational corporations such as Tyson, JBS-Swift, and Cargill that control a majority of the market.

Misconceptions or lack of knowledge about the painfulness of procedures and how to identify pain in farmed animals are additional obstacles to the use of analgesia in farmed animals, as are entrenched customs and the lack of laws governing the treatment of animals in agriculture.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Alternative, high-welfare farming allows animals raised for food to have a life free of unnecessary pain and suffering, and the opportunity to exhibit normal behaviors.