International transport by sea vessel can threaten an animal’s welfare, particularly for long-distance journeys, such as from North America to Asia. The toll on farm animals during international transport is likely to be exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, given the potential for longer journeys and delays in entering import countries—both of which would entail extended confinement under stressful conditions for these animals. Such prolonged stress can result in higher rates of disease and death.

AWI has been monitoring international export of farm animals from the United States for more than a decade, and last reported on this issue in the fall 2018 AWI Quarterly. Since then, we have received updated information on the US Department of Agriculture’s enforcement of its 2016 animal export rule. This article focuses on data from 2017 through the end of 2019.

The new rule, which responded to a rulemaking petition AWI filed in 2011, requires animals to be inspected prior to departure to ensure that they meet the World Organisation for Animal Health’s fitness-to-travel standards. The standards deem animals unfit if they are unable to stand or bear weight on all four legs, are blind in both eyes, have unhealed wounds, are extremely young, or are pregnant and in the final stage of gestation. The rule also includes animal accommodation standards for sea vessels and a requirement that operators submit reports at the conclusion of each voyage documenting the length of the trip and occurrences of “morbidity and mortality” (i.e., disease and death).

Since the rule went into effect, AWI has monitored animal shipments by submitting Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests for records relating to the USDA’s enforcement of the rule. Records we received indicate that from 2017 through 2019, an estimated 382,549 live mammalian farm animals (e.g., cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, rabbits, hares, and equines, but not birds) were exported from the United States to countries other than Canada and Mexico. An estimated 48,122 of these animals were shipped by sea vessel—nearly all of them cattle. (Others, such as pigs, sheep, and goats, are typically sent via airplane.)

Of the many countries that import farm animals from the United States by sea vessel, only a few import them in large numbers. For example, the top five countries importing cattle by sea (see figure 1) account for 87 percent of the total.

Figure 1: Top 5 Countries Importing Large Numbers of Cattle by Sea Vessel (2017-2019)

| Country | Number of Animals |

|---|---|

| Qatar | 11,727 |

| Kazakhstan | 9,494 |

| Vietnam | 8,477 |

| Turkey | 7,498 |

| Egypt | 4,478 |

Data source: Operator Reports and Export Reports, obtained by AWI via FOIA from USDA-APHIS

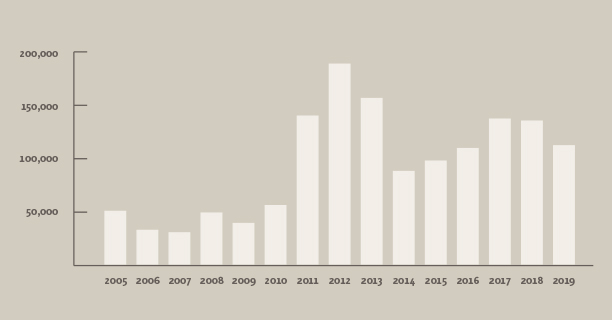

While the biggest spike in farm animal exports from the United States by air or sea occurred between 2011 and 2013—482,747 animals—the nation continues to export large numbers of farm animals, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Number of Live Mammalian Farm Animals Exported from the United States to Countries Other than Canada and Mexico (2005–2019)

Data Source: Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau, Foreign Trade Statistics

The USDA’s FOIA responses to AWI contained 37 export health certificates for animals shipped by sea 2017–2019, but only 24 had corresponding operator reports documenting the number of animal deaths during the voyage. A number of records appear to be missing relating to the export of goats, sheep, and lambs. According to the US Census Bureau’s Foreign Trade Statistics, from 2017 through 2019, approximately 59,000 goats, sheep, and lambs were exported internationally (excluding those sent to Canada and Mexico), but the records we received document only 1,001—less than 2 percent of the total.

The records we did receive indicate that, from 2017 through 2019, 287 farm animals died during international transport by ocean vessel. Given the volume of missing records, however, the actual number is likely higher. For these 287 animals, the leading causes of death include injury due to bad weather, pneumonia, gastrointestinal issues, and pregnancy-related conditions. Only one record reported on disease occurrence, even though this information is required by the regulations.

Cattle were stricken with disease due to pregnancy-related conditions during several shipments. The USDA’s rule prohibits transport of pregnant farm animals “in the final 10 percent of their gestation period at the planned time of unloading in the importing country.” We have contacted the USDA to encourage it to better enforce this provision to prevent avoidable deaths during transport. We also asked the department about the lack of operator reports for some shipments and about some operators’ failure to report on morbidity.

As it stands, the records indicate that the volume of animals being exported from the United States by sea is comparatively low. Although the mortality rate for one journey exceeded 3 percent, the average rate of mortality was far below that, at just 0.6 percent. No especially egregious incidents appear to have taken place in the wake of the 2016 amendments to the USDA’s live animal export regulations, but continued investigation is necessary, particularly in light of the missing records.