Marine animals use sound to navigate, communicate, find food, locate mates, and avoid predators. Flooding their world with intense sound interferes with these activities and results in serious—sometimes fatal—consequences. Anthropogenic (human-generated) noise levels in the marine environment are increasing at an alarming rate. In some areas, noise levels have doubled every decade for the past 60 years. There is mounting concern that noise proliferation poses a significant threat to marine ecosystems and the survival of marine mammals, fish and other ocean wildlife.

AWI is an active partner of the International Ocean Noise Coalition, an alliance of over 150 groups working for international regulation of ocean noise. With representatives on every continent, IONC was created to establish a global approach to combating human-generated ocean noise. Since 2005, AWI has been working with IONC at the United Nations and in other international forums to raise awareness about the issue and ultimately to advocate for ways to address the problem.

Although noise is a recognized form of pollution, sources of noise in the marine environment are not regulated at an international level. In the past half-decade international institutions have begun to recognize the threat it poses to marine wildlife and have been calling for precautions in the creation of anthropogenic ocean noise.

Find out more about the impacts of ocean noise on marine wildlife, the sources of human-generated ocean noise, and the international bodies and agreements addressing anthropogenic ocean noise.

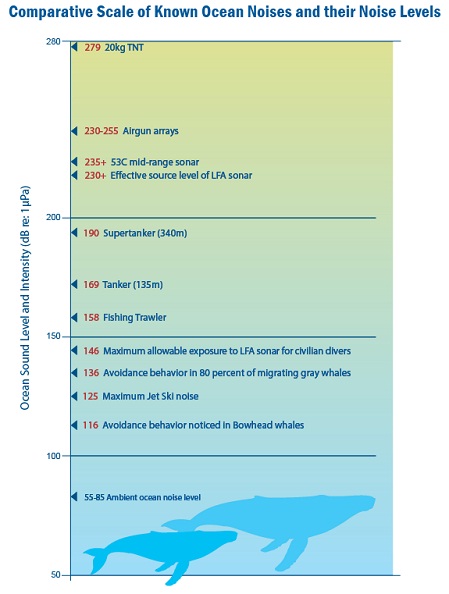

How Loud is Anthropogenic Ocean Noise?

Sound energy is measured in decibels (dB) relative to the threshold of human hearing. The decibel scale is logarithmic, which means 20dB is not merely twice as loud as 10dB, but rather represents 10 times more sound energy; 30dB is 100 times more. In the table below, the supertanker produces over 100 times more sound energy than the tanker.

Ben White

Former AWI consultant Ben White was passionate about defending the oceans and their inhabitants against ocean noise. Ben’s last direct action was to oppose a seismic experiment off the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico. The experiment was conducted by the Research Vessel Maurice Ewing, funded by the National Science Foundation, and took place in January 2005. Ben died later that July.

Impacts of Ocean Noise on Marine Wildlife

Impacts on Marine Mammals

Marine mammal strandings are the most visible impacts of anthropogenic noise. Such incidents, however, only give a snapshot of the real problem, since affected animals may not beach and some may suffer long term effects that are not measurable. Population level impacts have occurred in stranding incidents, such as the mass stranding of beaked whales in 2000 in the Bahamas. This stranding—caused by the passage of a single US Navy ship using active mid-frequency sonar—resulted in 17 deaths and the loss of a well-studied population of beaked whales from the area.

Negative responses to anthropogenic noise have been demonstrated in at least 27 species of marine mammals in scientific studies. Effects can include:

- Mortality or serious injury caused by hemorrhaging around the brain, air cavities, lungs and other organs;

- Mortality or serious injury caused by the formation of nitrogen bubbles in the bloodstream, leading to embolism;

- Temporary or permanent loss of hearing, impairing an animal’s ability to perform essential life functions, such as communication, avoiding predators, avoiding vessel traffic, finding mates and catching prey ;

- Stranding caused by the above factors;

- Avoidance behavior, which can lead to abandonment of habitat or migratory pathways and disruption of mating, feeding or nursing;

- Aggressive behavior, which can result in injury;

- Masking of biologically meaningful sounds, such as the call of predators or potential mates; and

- Depletion of prey species.

Impacts on Fish and Other Marine Species

Intense ocean noise damages fish and, consequently, fisheries. Research so far has indicated reactions to noise in 21 species of fish. Since anthropogenic ocean noise can travel hundreds of miles from its source, the potential impact to fisheries from domestically unregulated foreign noise activities is immense. This could have significant effects on national economies, commercial fisheries and local fishing communities. Harmful effects include:

- Extensive damage to fish ears and hearing;

- Catch rates reduced 40–80% and fewer fish near seismic surveys reported for cod, haddock, rockfish, herring, sand eel and blue whiting;

- Disruption in schooling structure, swimming behavior, and, possibly, migration in bluefin tuna;

- Secretion of stress hormones in several fish species in the presence of shipping noise;

- Alteration of gene expression in the brain of codfish following airgun exposure;

- A significant increase in heart rate in embryonic clownfish with exposure to noise;

- Negative impacts on sand eels from airguns;

- Avoidance behavior in capelin and eels when exposed to noise;

- A reduction in growth and reproduction in brown shrimp exposed to noise;

- Bruised organs, abnormal ovaries, smaller larvae, delayed development and stress in snow crabs when exposed to seismic noise; and

- Increased food consumption and histochemical changes in lobster after exposure to seismic noise.

Sources of Human-Generated Ocean Noise

Commercial, scientific, military and recreational marine activities can all generate noise sufficient to impact marine wildlife.

Explosives

Explosives are detonated in the ocean by the military, scientific researchers, and the oil and gas industry for demolition purposes, seismic exploration, or testing of equipment—such as shipshock trials, whereby ships are deliberately struck with explosives to test their durability. Explosions are created by chemical devices; they cause extremely high noise levels in the wideband frequency range and are characterized by rapid rise times—a sudden burst which can permanently damage hearing structures.

Seismic Airguns

Seismic airgun arrays are used primarily for oil and gas exploration and research purposes. The airguns produce sound by introducing air into the water at high pressure, usually directed toward the sea floor, with up to 20 guns being fired in synchrony, while “streamers” of hydrophones listen for echoes. Seismic surveys with airguns can last for many weeks at a time. During the surveys, every airgun in the array produces a pulse of noise lasting 20 to 30 milliseconds which is repeated every 10 seconds, often for 24 hours a day.

Military Sonar

Active sonar is used by military vessels during exercises and routine activities to hunt for objects in the path of the vessel. These Mid-Frequency Active (MFA) and Low-Frequency Active (LFA) sonar systems usually emit 100-second-long “pulses” of sound that can be deployed for hours and are designed to focus as much energy as possible in narrow ranges in a horizontal direction. LFA sonar is a type of long-range surveillance sonar that saturates thousands of cubic miles of ocean with sound. Frequencies commonly used by sonar systems range from around 0.1 to 10 kHz, with source levels in excess of 230 decibels.

Ship Traffic

Ships produce noise that generally falls in the low frequency band, between 10 Hz and 1 kHz—capable of propagation over immense distances in all directions. These low frequencies coincide with the frequencies used, in particular, by baleen whales, fish, seals, sea lions and dolphins for communication and other biologically important activities. Ships generate sound primarily by propeller action, hull-mounted machinery, and hydrodynamic flow over the hull and the flexing of the hull. Over 90 percent of world trade is transported by ship, effectively producing an ever-present and rising aural “fog” that masks crucial natural sounds and is the most pervasive source of ocean noise today. In general, noise increases with vessel speed.

International Bodies and Agreements Addressing Anthropogenic Ocean Noise

AWI is an active partner of the International Ocean Noise Coalition, an alliance of over 150 groups working for international regulation of ocean noise. With representatives on every continent, IONC was created to establish a global approach to combating human-generated ocean noise. Since 2005, AWI has been working with IONC at the United Nations and in other international forums to raise awareness about the issue and ultimately to advocate for ways to address the problem.

Although noise is a recognized form of pollution, sources of noise in the marine environment are not regulated at an international level. In the past half-decade international institutions have begun to recognize the threat it poses to marine wildlife and have been calling for precautions in the creation of anthropogenic ocean noise.

The following international bodies and agreements address anthroprogenic ocean noise.

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the most far-reaching treaty governing the global marine environment. UNCLOS already provides a solid basis for treating harmful, human-generated noise as a form of pollution that must be reduced and controlled. The agreement defines the term “pollution” as “the introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine environment..., which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources...” (Art. 1(1) (4)).

In his 2005 report to the General Assembly, the UN Secretary General listed anthropogenic underwater noise as one of five “current major threats to some populations of whales and other cetaceans,” and included noise as one of the 10 “main current and foreseeable impacts on marine biodiversity” on the high seas.

The UN General Assembly (GA) has passed successive resolutions to address noise, encouraging “further studies and consideration of the impacts of ocean noise on marine living resources” (2005, 2006 and 2007), and “requesting the Division [DOALOS] to compile the peer-reviewed scientific studies it receives from member states [and IGOs in 2009] and to make them available on its website” (2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009). In 2010, the GA Oceans resolution noted underwater noise as a potential threat to living marine resources and affirmed the importance of sound scientific studies in addressing the issue, while the GA Fisheries resolution encouraged further studies, including by the FAO, on its impacts on fish stocks and fishing catch rates.

International Maritime Organization

The IMO recognized the harmful effects of ship-generated ocean noise at the 57th meeting of its Marine Environment and Protection Committee. The issue was later given a dedicated agenda item and work program to develop technical guidelines on ship-quieting technologies as well as potential navigation and operational practices. The 2010 meeting agreed to continue the work and develop a draft guidance document “to reduce the adverse impact of ships’ noise.”

The European Parliament and European Union

The European Parliament adopted a resolution in 2004 calling on member states to urgently restrict the use of high-intensity sonar in waters under their jurisdiction until a global assessment of their cumulative environmental impact on marine mammals, fish and other marine wildlife had been completed. In 2008 the EU took up the issue with its Marine Strategy Framework Directive, representing the first international legal instrument to explicitly include man-made underwater noise within the definition of pollution (Article 3 (8)). The Directive lists “the introduction of energy, including underwater noise, at levels that do not adversely affect the marine environment” among the criteria to achieve Good Environmental Status (Annex I (11)) by 2020. Commission Decision 2010/477/EU(2) identified low and mid-frequency impulsive sound and continuous low frequency sound as potentially impactful on marine mammals and other marine wildlife.

Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic and North Seas (ASCOBANS)

ASCOBANS' 1994 Conservation and Management Plan set forth mandatory conservation measures to be applied to cetaceans. In 2003, a resolution requested parties to take steps to reduce the impact of noise on cetaceans from seismic surveys, military activities, shipping vessels, acoustic harassment devices and other acoustic disturbances. In 2006, ASCOBANS passed a second resolution on ocean noise, requesting that member states, inter alia, introduce guidelines on measures and procedures for seismic surveys and develop effective mitigation measures to reduce disturbance of, and potential physical damage to, small cetaceans. In 2009 it passed another resolution to mitigate adverse effects from noise generated by offshore renewable energy construction projects.

International Whaling Commission

The Scientific Committee of the IWC, at its 2004 meeting, stated that there is compelling evidence implicating anthropogenic sound as a potential threat to marine mammals, and that this threat is manifested at both regional and ocean-scale levels that could impact populations of animals. The body called for multinational cooperation to monitor ocean noise, and to develop basin-scale and regional noise budgets. Noise has been included in the body’s work since then and in 2009, ocean noise was identified as a priority issue for cetacean research.

Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS)

A 2004 ACCOBAMS resolution recognized man-made ocean noise as a dangerous pollutant that can disturb, injure and kill whales and other marine species. It called on member nations to avoid use of anthropogenic noise in certain areas; to research the issue, including on alternative technologies; and to require the use of best available control technologies and other mitigation measures, in order to reduce adverse impacts. A subsequent resolution adopted in 2007 established a working group to develop tools to assess noise impacts on cetaceans and mitigation measures, while urging parties to adhere to a set of principles to reduce noise impacts. In 2010 a third resolution promulgated guidelines to address noise impact on cetaceans in the ACCOBAMS area.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CDB)

The 14th Conference of the Parties to the CBD in Nagoya, Japan, recognizing underwater noise as being beyond merely a “new and emerging” issue, requested its Secretariat to compile and synthesize scientific information on anthropogenic underwater noise and its impacts on marine and coastal biodiversity and habitats.