The cross-country movement of farmed animals has increased steadily over the past several decades, as animal agriculture has shifted toward large-scale industrial production under the control of fewer companies and relying on separate, specialized facilities to handle various stages of production. As a result, each year, millions of farmed animals (not counting poultry) are routinely transported for a variety of purposes, including breeding, grazing, feeding, marketing, and slaughter.

Transport is recognized as one of the most stressful times in a farmed animal’s life. In addition to the vibration, noise, fumes, and unfamiliar environments, transported animals often experience prolonged food and water deprivation, intense crowding, exposure to extreme heat and cold, and physical stress and injuries from rough handling and having to balance in a moving truck.

Studies have shown that stress, particularly when prolonged, lowers an animal’s ability to resist infection. Consequently, stress during transport has significant impacts not only on animal health and welfare, but also on food safety (when diseased animals are slaughtered), and antibiotic resistance (when large quantities of antibiotics are used to treat or ward off disease).

Transport is difficult even when the animals are healthy and physically fit, but the stressors are amplified for young, weak, diseased, or injured animals. The young and those already in a state of poor health are less able to cope with the challenges associated with transport and often experience further deterioration in condition.

Currently, the only federal law in place to protect animals in transit is the “Twenty-Eight Hour Law,” which requires animals transported domestically for 28 hours or more to be offloaded for food, water, and rest for five consecutive hours. This law, however, is poorly enforced. Particularly vulnerable animals, such as “cull” animals and neonatal “surplus” calves, have less economic value than their “market” counterparts—thus, their welfare during transport is even less of a priority to producers and carriers.

Cull Animals

Cull animals are those removed from a herd and sent to slaughter due to age, illness, or other infirmity affecting productivity. Dairy cows—typically culled once age or ill health leads to diminished milk production or fertility—are at high risk of lameness and other serious ailments. Cull breeding sows are similarly prone to lameness or other painful conditions.

Because these animals commonly develop numerous health issues due to age and the rigors of their time in production, they are more likely to experience poor welfare outcomes during transit—significant pain, becoming nonambulatory, even dying en route. Cull animals are the most at risk for being transported while unfit, and peer-reviewed research indicates that they are often transported in this condition. This is unsurprising, as they have no meaningful legal protection, and there are no incentives for producers to stop transporting unfit animals.

Cull animals, in fact, are regularly transported long distances, as only a limited number of slaughterhouses accept them. Although the US Department of Agriculture does not track the movement of cull animals to slaughter, it does record the number slaughtered. The most recent USDA data indicate that, in 2022, more than 3 million cull dairy cows, more than 3 million cull sows, and nearly 300,000 cull boars were slaughtered at federally inspected plants.

Young Dairy Calves

In the US dairy industry, young calves are often transported soon after birth. A portion of the female calves (referred to as “replacement heifers”) are reared off site by specialized operations until they are ready to give birth and produce milk. The remainder, as well as the males, are “surplus” and usually slated to become veal or “dairy beef.”

Transporting neonatal calves over long distances is particularly troublesome, as it significantly increases the risk that they will contract disease or die during or shortly after shipping. Several contributing factors are identified in the scientific and veterinary literature, including (1) immature immune function in young calves, (2) immunosuppressive effects of transport stress, (3) high levels of pre-transport illness and disease in young calves, and (4) mixing of calves from different facilities, resulting in exposure to novel pathogens.

Records obtained by AWI illustrate the significant toll transport takes on young calves. In one example, USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service personnel at a slaughter plant in Rupert, Idaho, documented the mortality of “bob veal” calves (under 3 weeks old) transported from California on journeys that likely lasted 9–12 hours. A staggering 18.5 percent loss, on average, was reported on dozens of shipments that occurred over an 18-month period. Dead-on-arrival calves made up roughly two-thirds of the reported losses; the remainder were calves who arrived “non-ambulatory, disabled” and were thus euthanized.

Calves not transported directly to slaughter, but rather shipped elsewhere to be raised as replacement heifers or dairy beef, are also at increased risk of illness and death. These calves are routinely administered antibiotics—both to buffer their systems against the stressful conditions and to treat and contain disease in the weeks after transport, thereby increasing the risk of creating antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

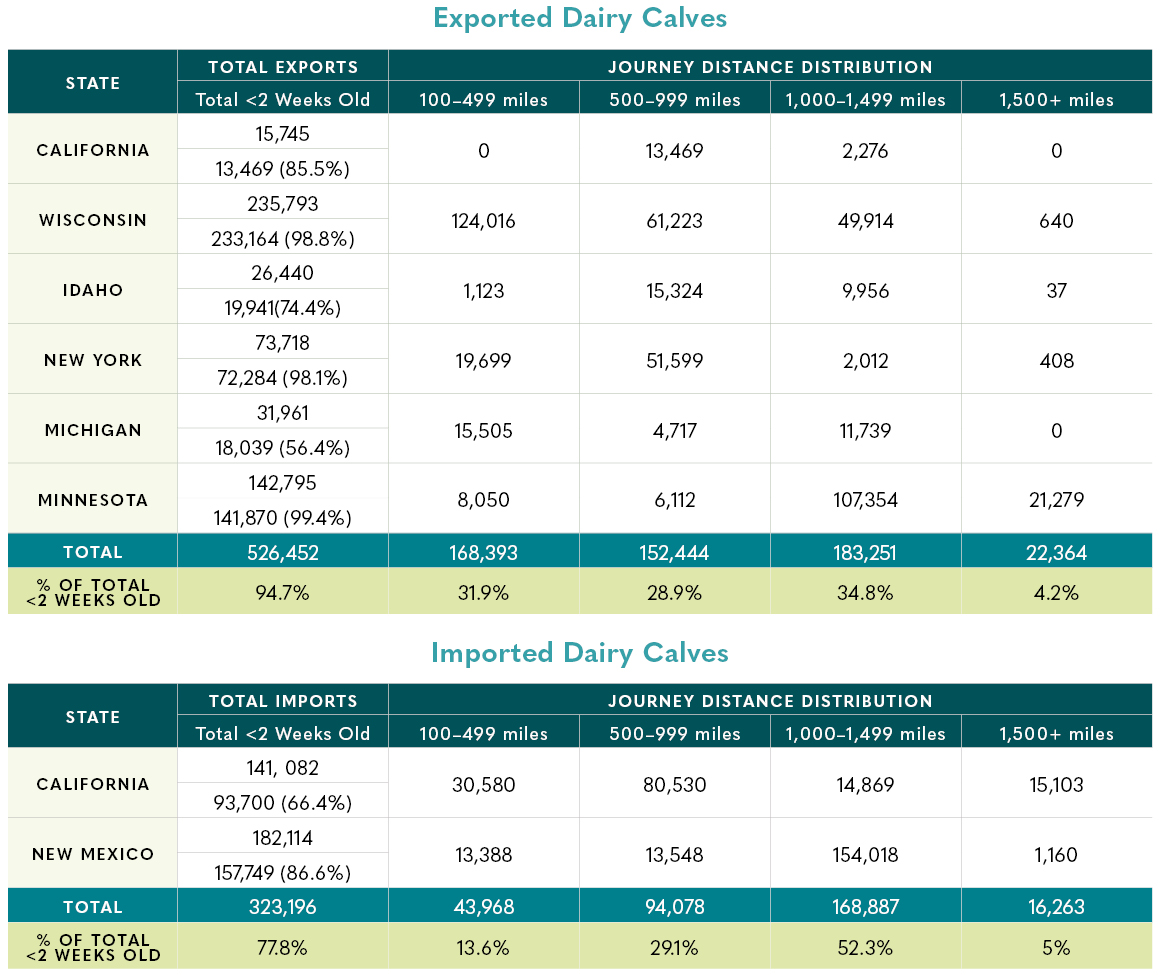

As with cull animals, the USDA does not track the number of neonatal calves transported interstate. However, AWI research revealed that the industry routinely subjects hundreds of thousands of young, unweaned calves to stressful journeys of up to 1,000 miles or more throughout the country.

The Investigation

AWI obtained export records from six of the 10 largest dairy-producing states (California, Minnesota, New York, Michigan, Idaho, and Wisconsin) as well as import records from two states with dozens of calf ranches (New Mexico and California). These records revealed that the six exporting states shipped more than 525,000 calves less than a month old on journeys of over 100 miles, with 39 percent of those traveling over 1,000 miles—a minimum of 14 hours.

To confirm what the records revealed, AWI partnered with the nonprofit organization Animals’ Angels to monitor a truckload of 1-week-old calves on a 1,113-mile journey from a mega-dairy in Minnesota to a calf ranch in New Mexico. Investigators followed the calves as they traveled 19 hours through Minnesota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico.

The investigators documented the calves’ condition on two occasions, once about two hours into the trip and again nine hours later. During the first observation, the investigators noted ear tags confirming the calves were around 1 week old, as well as the presence of umbilical cords on some, meaning their navels were unhealed and could easily become infected. Some of the calves were observed being stepped on by other animals due to overcrowding on the truck. At the 11-hour mark, all the calves were standing, and many were bellowing in the 100°F heat—a sign of distress. The investigators were unable to observe the animals’ condition during the final eight hours of the journey or during unloading at the calf ranch in New Mexico.

The Solution

The amount of suffering an animal endures and the possibility of death during transport depend primarily on two things: the conditions of transport (including stocking density, provision and condition of bedding, trailer design, journey duration, and weather) and the animal’s fitness to travel. Because of their delicate physical state, neonatal calves and many cull animals are unfit—they are likely to suffer and more likely to die en route.

The regular practice of transporting unfit animals violates the animal welfare code of the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), which, along with regulations of Canada, the European Union, Australia, and the United Kingdom, contains criteria for assessing the fitness of animals for transport. Although all transport poses a risk to animal health and welfare, particularly if the journey is very long, this risk can be substantially decreased if fitness-to-travel requirements are implemented and enforced.

In response to a rulemaking petition submitted by AWI in 2011, regulations governing the export of live animals were amended in 2016 to include fitness-to-travel requirements for all farmed animals exported from the United States, except those traveling overland to Canada or Mexico. AWI is now petitioning the USDA to establish fitness-to-travel requirements for cull animals and neonatal calves in transit within the United States. The petition specifically requests that the USDA prohibit the interstate transport of neonatal and cull animals who are (1) sick, injured, weak, disabled, or fatigued, (2) have an unhealed navel, or (3) have a body condition that would result in poor welfare because of the expected climatic conditions.

These three criteria are particularly relevant to vulnerable animals and are drawn directly from the WOAH code chapter on the transport of animals by land. AWI is asking the USDA to further require that all neonatal and cull animals be accompanied by a certificate of veterinary inspection indicating that a veterinarian has confirmed fitness to travel based on these criteria. Such certificates are already required by many state and federal regulations for certain animals transported interstate—including those neonatal calves not sent directly to slaughter—but are typically not required for animals transported directly to slaughter and thus not required for most cull animals.

Take action

Encourage the USDA to grant the petition. Meanwhile—even as we seek reforms to ease suffering within the system—consumers can avoid contributing to the plight of these vulnerable animals by choosing plant-based alternatives to meat and dairy.