Accredited zoos, aquariums, marine theme parks, and swim-with-dolphin operations—places that naturally concentrate large groups of people—were among the first tourism venues to close their doors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. By May, over 90 percent of facilities belonging to the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums had been closed to the public.

The future of publicly traded theme parks generally is uncertain; SeaWorld—the largest marine theme park in the United States—saw its stock tumble after the documentary Blackfish was released. As the company ended its orca breeding program and shifted its emphasis to rides, the stock largely recovered. Now, however, SeaWorld stock has declined to its lowest level ever. On March 30, the company announced it would furlough 90 percent of its staff. This left only a small number of people across multiple parks to care for more than 23,000 animals, from invertebrates to the famous orcas. (Two of the parks were planning to reopen mid-June; the California park has not yet indicated a reopen date.)

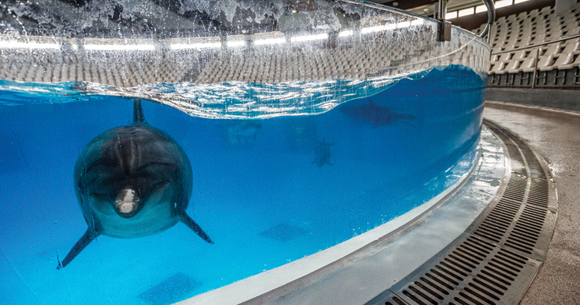

With countless human lives at stake, physical distancing rules may need to be maintained, at least to a partial degree, for the foreseeable future. This is tourism’s high season in the northern hemisphere. Under these circumstances, the distressing reality is that some (perhaps many) facilities will cull their animals. It will simply become untenable economically to continue to feed them if the facilities are generating no or reduced revenue. Even species with individual (and significant) economic value, like performing whales and dolphins, could face this outcome, as they are also very expensive to keep.

While many might imagine that releasing captive animals to the wild or sending them to sanctuaries would be the obvious alternative, the unfortunate truth is that most animals in zoos or aquariums are now utterly dependent on humans feeding them, and there aren’t enough sanctuaries to take them all. And sanctuaries are also facing economic hardships during this time. The cold fact is that these animals have nowhere to go, and putting wildlife at the direct mercy of the dollar is a recipe for disaster whenever the economy is disrupted, for whatever reason. Does the entertainment and recreational value of such facilities really justify this fate?

On the other hand, free-ranging whales and dolphins may benefit—though perhaps only temporarily—if the pandemic results in a severe curtailing of the live wildlife trade. Marine mammals are also potential sources of novel pathogens that can jump to humans, and it would be wise for society to protect itself—and the animals—by ending capture and handling of belugas, bottlenose dolphins, and orcas, all of which are still often taken directly from the wild for display in several countries. Certainly for now, the whales in Russia who were destined for oceanariums in China are safe from the catchers’ nets.

International and regional zoo associations are considering, or advising their members about, approaching governments for pandemic relief funds. AWI urges any authorities reviewing bailout proposals for facilities with marine mammal exhibits to consider putting conditions on funding, such as public transparency on management decisions (including those involving culling) and a ban on breeding of cetaceans. Ideally such a ban would be permanent, as then public funds would not be supporting the continued captive holding of wide-ranging species inherently unsuited to confinement in small spaces.