On September 10, the 67th meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), hosted by the government of Brazil, opens, with AWI again in attendance. This meeting looks to be one of the most contentious and action packed in years, with Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) quotas up for renewal, including that of the United States, a call for a whale sanctuary in the Southern Hemisphere, and a call from Japan to rewrite the IWC ruling documents in a move to overturn the moratorium on commercial whaling that has stood for over 30 years.

Even though IWC member countries Japan, Norway, and Iceland continue to whale for commercial purposes in contravention of the commercial whaling ban, many tens of thousands—if not hundreds of thousands—of whales have been saved because of the moratorium. Today, whales are also facing additional human threats, including climate change, bycatch in fishing nets, ocean noise, plastic debris, and other forms of pollution. In the period since the adoption of the moratorium in 1986, the IWC has evolved into the premier body for whale conservation, with active working groups on issues including bycatch, ship strikes, whale watching, and the role of whales in the marine ecosystem.

Indigenous people from four countries have ASW quotas. Their governments—Russia, the United States, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Greenland (represented by Denmark)—are requesting the renewal of their expiring ASW quotas for the next six years, but they are also seeking new rules that would allow their quotas to renew automatically, in perpetuity. They are grouping their quota renewal requests—which include increases for Greenland and Russia—into a single package that must be voted on together, and are also seeking the right to carry forward unused strikes from one quota block to another. While AWI does not oppose ASW to meet genuine cultural and nutritional subsistence needs, we take issue with the proposed quota renewal package and have submitted extensive comments to the IWC on this request.

Japan—which previously orchestrated a denial by the IWC of the United States’ ASW quota—is chairing this IWC meeting. Japan is proposing a series of measures that would precipitate a resumption of commercial whaling, including an amendment of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling to permit a simple majority (rather than the current three-fourths majority), to alter quotas and make other important decisions.

Brazil is hoping the IWC will support its proposal to create a massive whale sanctuary in the South Atlantic and has proposed several other conservation initiatives.

The stage is set for a difficult meeting. AWI’s priorities, in addition to avoiding any increase in whale killing, include making progress on the mitigation of bycatch—the biggest killer of cetaceans (including dolphins and porpoises)—and increasing scientific understanding of the ecological role that whales play in maintaining healthy and productive oceans.

Whales are integral species in the marine ecosystem and play an essential role in maintaining healthy oceans. However, whales and dolphins, as well as their environment, face an increasing number of threats, primarily from anthropogenic sources. The cumulative effects of climate change, bycatch, entanglements, ship strikes, hunting, and pollution (from noise, chemical sources, and marine debris) are severe, and underscore the need to maintain the commercial whaling moratorium and for global cooperation to ensure cetaceans’ survival. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) plays a vital role in the current and future survival of the world’s whales.

In addition to the vital role whales serve in the ecosystem, helping to combat climate change and amplifying productivity, thereby benefiting fisheries and enhancing food security, whales play an important role in local economies. Responsible, sustainable whale and dolphin watching industries make important contributions to island and coastal states, particularly for developing economies, and we congratulate the IWC for the production of its new online Whale Watching Handbook.

AWI specifically supports, and we urge contracting governments to support, IWC/67/05 on anthropogenic underwater noise, IWC/67/10 on Creating a South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary, AWI/67/11 on ghost gear entanglement, IWC/67/13 on the Florianópolis Declaration, and IWC/67/17 on advancing the work on the role of cetaceans in ecosystems. We also applaud and support the work of the bycatch, ship strikes, and ecosystem functioning working groups.

All whaling is inherently cruel because even the most advanced whaling methods cannot guarantee an instantaneous death or ensure that struck animals are rendered insensible to pain and distress before they die, as is the generally accepted standard for domestic food animals. The Animal Welfare Institute (AWI) recognizes however, that some indigenous peoples need to hunt whales in order to survive and is actively involved in deliberations about Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling to ensure that: (a) such whaling fulfills a legitimate and continuing cultural, nutritional, and subsistence need; (b) such killing is limited to only the number of whales needed; (c) the targeted whale populations can sustain such kills; (d) each whale is fully utilized by those responsible for the animal’s death and not traded commercially; (e) the whaling is conducted using the least cruel techniques available; and (f) continuing efforts are made to increase the efficiency of the hunt and reduce the amount of time it takes individual whales to die. AWI does, however, have grave concerns that the above conditions are not being met by all current aboriginal subsistence whaling operations.

Recent increases in the human consumption of aquatic wild meat and the use of dolphin meat as bait in commercial fisheries for sharks, crabs, and catfish, are alarming. Given that many of these commercially valuable fish species are already overexploited, fisheries using cetaceans as bait exacerbate concerns about the sustainability of the takes for both small cetaceans and fish stocks and call into question the long-term survival and viability of all affected species. We refer member governments to our 2018 joint report “Small Cetaceans, Big Problems” (with Pro Wildlife and WDC) which calls on the IWC to: increase funding for the Scientific Committee’s Marine Bushmeat Working Group and expand its mandate to be global; establish a comprehensive and detailed database and informal reporting mechanism on small cetacean hunts for general use by the IWC, including by the Scientific Committee; include products derived from small cetaceans in the calculation of need for ASW catch limit requests; and adopt a resolution at IWC 68 on directed hunts of small cetaceans and the commercial use of bycaught animals.

In summary, given the precarious situation that our oceans are facing now compared to 30 years ago when the moratorium came into effect, the cumulative impacts on cetaceans from many anthropogenic threats, the inherent cruelty of whaling, and the vital role that whales play in maintaining healthy marine ecosystems, AWI believes that the commercial whaling moratorium must remain intact. AWI is therefore strongly opposed to IWC/67/08 (“The Way Forward of the IWC”).

The meeting was opened by the IWC chair, Mr. Joji Morishita of Japan, welcoming participants and introducing the Brazilian environment minister to welcome attendees. Opening statements were then made by two new parties to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling—São Tomé and Príncipe and Liberia—followed by statements from Australia and Japan. The former clearly stated its opposition to overturning the moratorium on commercial whaling while Japan urged parties to acknowledge sustainable whaling, for parties to respect each other, and for whaling and anti-whaling to coexist within the IWC. Japan’s statement received a round of applause from some delegates.

After the IWC secretariat gave a review of countries that were not paid up and are therefore not yet voting members, the chair laid down some rules on the coming discussions, including the protocol for interventions and a suggestion for breakout groups to form if necessary to wrestle with agenda items. He then reviewed the documents for the meeting and the agenda was adopted.

Next, the outgoing chair of the Scientific Committee provided a review of the work of the committee during the past two years, and its work plan for the next decade.

After the lunch break a report on the work of the Conservation Committee was presented by the committee chair, Dr. Lorenzo Rojas Bracho of Mexico. The committee’s past accomplishments included work on bycatch mitigation, whale watching (including the development of an online whale watching handbook), conservation management plans, ship strikes, marine debris, marine noise, and cetaceans and ecosystem functioning.

A few countries asked to respond to the Conservation Committee report. These included Austria (speaking on behalf of the European Union), which praised the committee’s work and supported the proposal for it to hold annual meetings, and New Zealand, which urged all IWC members to participate in the committee’s work. (Certain whaling nations do not participate in the Conservation Committee—neither attending its meetings nor participating in its working groups.)

The meeting then moved onto “governance review”—a new agenda item pertaining to a review of the IWC and its functionality, undertaken by a panel of experts convened since the last plenary meeting in 2016. One of the panel members presented the panel’s recommendations. These addressed strengthening the IWC bureau, maintaining a biannual meeting, strengthening intercessional communications, improving communication between the Scientific Committee and the IWC, methods to improve conflict resolution, improving the rules of procedures for the bureau, improving communications with other international bodies, and hiring a legal expert, among other issues.

The chairs of the Scientific Committee, Conservation Committee, Finance and Administration Committee, and Operational Effectiveness Working Group then responded to the report presentation, followed by general comments from the floor. After a coffee break the meeting resumed for the last session of the day to discuss Resolution IWC/67/14: Draft Resolution on the Response to the Independent Review of the International Whaling Commission. Despite some initial opposition from Japan—which noted that most of the proponents of the resolution are not developing nations and are pro-conservation—Japan supported its passage but noted further that the level of response to the panel’s inquiries was not high and its passage should not open the way to abuse of the powers it provides. The resolution passed by consensus to a round of applause.

The chair then moved onto agenda item 6: proposals to amend the schedule related to the setting of Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) quotas, creation of a South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary, and setting catch limits for certain whale species (thus overturning the moratorium on commercial whaling).

The United States introduced the ASW schedule amendment package, comprising a one-time, seven-year extension of catch limits, carryover provisions for unused quotas year on year, and an automatic renewal of the quotas at the end of the quota block. Brazil then introduced its schedule amendment to establish a South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary, on behalf of Argentina, Brazil, Gabon, and Uruguay. Finally, Japan introduced its schedule amendment package to set catch limits on certain whale species and its proposal to establish a sustainable whaling committee (including for ASW).

The chair remarked that the scheduled amendments had now been introduced and encouraged discussion in the coming days—suggesting that the evening’s coming reception hosted by the government of Brazil would be a good starting venue for those discussions. He then quickly moved to agenda item 7 and asked that the meetings’ resolutions be introduced.

On behalf of the European Union member states, Austria introduced a resolution on human-generated underwater noise, which was quickly cosponsored by Switzerland and Monaco. Ghana then introduced a controversial resolution on food security related to whales; similar resolutions have been unsuccessfully proposed in previous meetings. Brazil introduced three resolutions, on ghost gear entanglement among cetaceans, the UN 2030 Agenda (sustainable development goals), and the “Florianopolis Declaration”—a resolution on the role of the IWC in the conservation and management of whales in the 21st century. Finally, Chile introduced a resolution on advancing the IWC’s work on the role of cetaceans in ecosystem functioning.

The chair announced the close of day one, encouraging member countries to read all the proposals put forward for further discussion during the rest of the meeting. After a few reminders about submitting statements to the IWC, the chair thanked everyone and closed the meeting for the day.

The meeting started a little after 9 a.m., with the chair thanking the government of Brazil for the lively reception the previous evening and welcoming delegates. After dealing with a few administrative details and comments on the progress of agenda items, the chair continued. He announced that he had been asked if agenda item 16.1, the proposed schedule amendment on the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary (SAWS), could be moved up by the Brazilian proponent due to a scheduling conflict.

The meeting then proceeded with Brazil urging parties to join together in supporting this proposal and asking for a very brief debate. The chair then announced that South Africa had become a cosponsor and opened the floor. Japan thanked Brazil and then stated that such a proposal has been repeatedly rejected at previous meetings due to no scientific basis for creating such a sanctuary. Therefore, Japan has not supported and cannot support this proposal. He continued that the IWC Scientific Committee has said that sanctuaries cannot protect whales, especially from threats such as climate change. Claiming that this proposal would lead the IWC towards conflict again, he stated that Japan opposes the SAWS proposal.

Numerous statements were made in favor of the proposal by Austria (on behalf of the members of the European Union), Mexico, Monaco, New Zealand, India, Gabon, Colombia, and Argentina. The United States also voiced its support early in the discussion, saying it fully supported the proposal as a way to advance whale conservation and that sanctuaries provide benefits such as whale watching opportunities for local coastal communities and provide opportunities for scientific research.

Countries against the proposal included Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, Norway, Cambodia, Benin, Liberia, Senegal, Togo, the Russian Federation, and Iceland. Brazil thanked those countries supporting the proposal and rebutted some of the negative comments. This was followed by a statement on behalf of the conservation nongovernmental organizations, including AWI, in support of the proposal. The chair then asked the proponents how they wished to proceed. Brazil said it would have preferred consensus but asked for a vote. The chair then asked for the vote to take place. The final result was 39 countries in favor, 25 against, and 3 abstentions. Since a three-fourths majority is needed to approve schedule amendments, the vote failed. Brazil thanked those who voted and the chair closed the session for a coffee break.

The meeting resumed with the chair introducing agenda item 8, Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW), one of the more contentious topics at this meeting. He first explained how he wanted to run this agenda item, referring to previous workshops and the recent subcommittee meeting that have taken place to date. Mr. Bruno Mainini of Switzerland then reported on the meeting of the ASW subcommittee, and specifically on the reports on meetings of the ad-hoc Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling Working Group (ASW WG). AWI has been involved in all of these meetings, actively participating when allowed. After the report, the chair opened the meeting for comments and Japan took the floor to voice its support for the reported results of the subcommittee on ASW, including the recommendations of the ASW WG. The United States thanked Dr. Mike Tillman for his outstanding leadership and the members of the ASW WG who had worked on these often-difficult topics. The chair asked if the IWC could endorse the conclusions and recommendations of the subcommittee and working group and received a consensus affirmative decision. The chair closed this agenda item after thanking Dr. Tillman for his work.

The commission then moved to the next ASW agenda items, the ASW Management Procedure, the ASW scheme, ASW catch limits, and the ASW voluntary fund. Argentina asked a question about photo ID information on whales hunted by St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The chair then closed for lunch, announcing that the ASW schedule amendments would start the afternoon session.

The meeting reopened with the chair of the ASW subcommittee reporting on the committee’s discussions on the ASW schedule amendment package.

The ASW subcommittee chair reported that there had been no consensus on the proposal in the subcommittee. The meeting chair then opened the floor for questions and comments and then moved to a discussion on the schedule amendment proposal. He invited the proponents to speak.

The United States then took the floor and introduced the Alaskan and Makah representatives, who commented on their portion of the proposed schedule amendment proposal, including referencing the 2002 denial of the quota for political reasons. The Russian Federation then took the floor to provide information on Russia’s portion of the schedule amendment proposal. All the native representatives spoke about the traditions associated with their whaling, with the Chukchi representative touching on the subsistence need and the lack of other foods in their community. Denmark came next and, after a brief comment about human rights, introduced the Greenland representatives, who spoke about their culture and dependence on whales. Finally, St. Vincent and the Grenadines spoke to urge support for the passage of its requested quota, despite presenting little information on the hunt.

After the chair opened the floor for comments, Japan spoke, stating that it could not find any reason to oppose the ASW bundle. Austria, on behalf of the European Union, thanked governments for the proposal, said that it supports ASW and the use of the precautionary principle to set ASW quotas—subject to the advice of the Scientific Committee and provided that the ASW is sustainable. Austria noted that the European Union is working diligently with ASW countries to reach an agreement, that it hopes that the final text will strike the right balance, and that it is working hard to make sure this is the case.

Korea mentioned its history of whaling and continued interest in whaling, despite ending the practice to comply with the moratorium. Other supporters of the proposal included the Solomon Islands, Senegal, Liberia, Iceland (asserting that the biological viability and sustainability of whale stocks is the only thing that matters and that people should not be categorized, everyone is equal, and that “we should not judge culture and diets”), Norway, Cambodia, Switzerland, Cameroon, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Antigua and Barbuda. The latter stated that, while it would not block consensus, it reserved its position on this schedule amendment pending discussions on the food security issue and sustainable whaling schedule amendment.

Chile pointed out its concerns with grouping the ASW quota requests into a package, which it stated makes it possible for weaknesses and flaws to be hidden in the package, and particularly expressed concern with the proposed increased quota request by Greenland. This view was supported by Costa Rica, Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, Uruguay, and Ecuador. Monaco said that it supports ASW but has concerns with the automatic renewal request—although it wants the IWC to be a functional body and hopes that consensus can be achieved. New Zealand stated that it can support the quotas if they are scientifically justified, but added that needs statements are important, that it is concerned with extended times to death, and that it encourages countries to help their natives to minimize times to death.

After the numerous government interventions, the chair opened the floor to intergovernmental organizations and nongovernmental organizations. The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO), which supports sustainable whaling, expressed some concerns about the carryover issue but generally supported the ASW proposal. Whaleman Foundation spoke on behalf of AWI and others against the Makah tribe quota request, primarily because of the Makah’s lack of a continuous need for whales. Humane Society International gave an intervention on behalf of a number of NGOs, including AWI.

The chair then asked the proponents of the proposal to take the floor. The United States announced that the four ASW countries would like to say they appreciate the communications with delegates and that it predicts that revised language may be ready by tomorrow. Denmark added its agreement on behalf of Greenland, and Russia then supported the comments of the United States and thanked the delegations for their active contributions to the language of the proposal. St. Vincent and the Grenadines supported the comments of Russia, Denmark, and the United States. The chair then stated that this agenda item would stay open overnight and summarized the work of the day. By midnight, the revised document had appeared on the IWC website.

The chair then announced an evening meeting of those delegates working on the food security resolution and closed the meeting. As was the case in the last IWC meeting, in 2016, nongovernmental organizations were allowed to participate in the drafting group on food security. AWI was one of three groups that joined the evening session.

Intervention by Claire Bass of Humane Society International on the ASW schedule amendment proposal, Tuesday September 8, 2018

Thank you Chair, I speak on the behalf of Humane Society International, American Cetacean Society, WWF, Animal Welfare Institute, The Whaleman Foundation, legaSeas, Fundación Cethus and Whale and Dolphin Conservation. The issues raised in this extensive package submitted are complex. I need to say at the outset that in making comments here, we do not seek to undermine or challenge the responsibility of the Commission to set quotas for those aboriginal communities who have a continuing, traditional dependence on whaling and the use of whales to meet their subsistence needs. Our comments are in the context of our interest in achieving the best conservation and welfare outcomes for whales, ensuring clarity and transparency, and maintaining the affirmative decision making role of the Commission in setting quotas of any kind.

After careful reflection, we believe that we understand why there is a perceived need for an 'automatic renewal. ’ In addition, we appreciate the arguments for more flexibility that have been advanced by subsistence whaling nations and the efforts made by proponents to address questions about the proposal. However, we do not believe that the proposal before the Commission safeguards the appropriate scrutiny and decision making powers that are intrinsic to the mandate of the Commission.

Most importantly, we have always understood and we feel confident in representing here that the Commission established and developed the category of whaling known as aboriginal subsistence whaling with the clear intention of it being managed separately and under different principles from whaling for commercial purposes. The primary difference is that ASW catch limits are based on need; specifically cultural, nutritional and subsistence cultural needs.

Unfortunately, as we look at what is proposed here we are now unsure that the Commission still understands that its responsibility is to review and grant subsistence whaling quotas to meet a specific need. The proposal’s sole dependence on the Scientific Committee’s sustainability advice is a significant departure from the Commission’s longstanding process of reviewing a range of relevant factors before deciding whether to approve ASW quotas. These factors have included matters that directly affect levels of need for whales including demographic changes and the availability of other food sources. Noting also the increasing and unpredictable impact of climate change on the flora, fauna and peoples of the high latitudes, we consider this is not the time to assume a ‘business as usual’ approach to the management of ASW in the Arctic.

In this room today the Commission must speak unambiguously to the Commission of the future. We urge this meeting to establish a clear, comprehensive and reasonable standard for reallocating aboriginal subsistence whaling quotas, a standard and directive that preserves the affirmative decision-making powers of the Commission. Such affirmative decisions must, we believe, continue be based on the Commission’s evolving understanding, respect for and appreciation of the needs of communities that depend on whales living in changing and degraded oceans.

Finally, Mr Chair, the many organisations with an animal welfare mandate at IWC67 wish to express serious concerns over the welfare outcomes for whales taken in the two hunts for which quota increases are sought. Data presented to the Commission this year shows that 21 whales taken during the 2016 and 2017 Russian gray whale hunt took over an hour to die, with one animal taking over three hours. These extended times to death should command serious efforts to improve hunt welfare, and we echo the remarks of New Zealand in calling for a commitment to improved weaponry and training. We would also strongly encourage a commitment from Greenland to support its hunters in West Greenland to revert to the use of harpoons instead of rifles as the primary killing method for minke whales.

The chair opened with an announcement that the meeting might be able to make a decision on the outstanding schedule amendment discussed yesterday (the ASW package), followed by the next items on the agenda, and possibly the discussions on the future of the IWC.

Antigua and Barbuda presented a report on the informal group formed the previous evening to discuss the food security resolution. It said progress had been made but the group needed to continue working, and it invited interested parties to meet again at a time to be determined.

Australia gave input on the report of the special permit working group that it chairs, and invited comments on the draft before it is presented to the meeting.

The chair then suggested creating a small group to work on the discussions concerning the way forward, but nothing further was discussed on this topic during the session.

Returning to the ASW schedule amendment, the chair commented that he understood substantial progress had been made on the package and invited the United States to present the revised document. Ryan Wulff of the US presented the changes.

Australia stated that it supports the traditional hunting rights of aboriginal people, recognizes that the text is a compromise, and accepts the good faith in which the text has been given. Austria, on behalf of the European Union, welcomed the progress that has been made and stated that the EU fully supports the revised package. South Africa stated that it fully supports the revised package. Grenada stated that it fully supports the package. Japan stated that it appreciates the hard work of the proponents to improve the process to address concerns of member states. It believes that the sustainable use of precious whale resources can be achieved. It strongly supported the proposal and urged adoption by consensus. Antigua and Barbuda expressed its support. India stated that it supports the proposal but urged that aboriginal peoples be slowly weaned away from their dependence on whales for food, similar to a program done for a number of tribes in India. This process should include developing whale watching as part of the process of looking for alternative livelihoods. Monaco expressed its support. Iceland stated that it supports the amended text and wanted to highlight the recognition that science-based decisions on sustainable use of marine resources has prevailed, and congratulated the countries that have been willing to compromise. Gabon stated that it supports the proposal and the intervention by India urging the ASW countries to seek alternate nonconsumptive use of whales in the future.

The representative from the International Union for Conservation of Nature said that there seems to be general support for the schedule amendment but that concerns have been expressed regarding the automatic renewal component. He suggested that while the main part of the package might be adopted, the automatic renewal part could be considered in the intervening period before the quota renewal due date.

With no further interventions, the chair announced that he didn’t believe there was a consensus and invited the proponents to say how they would like to proceed.

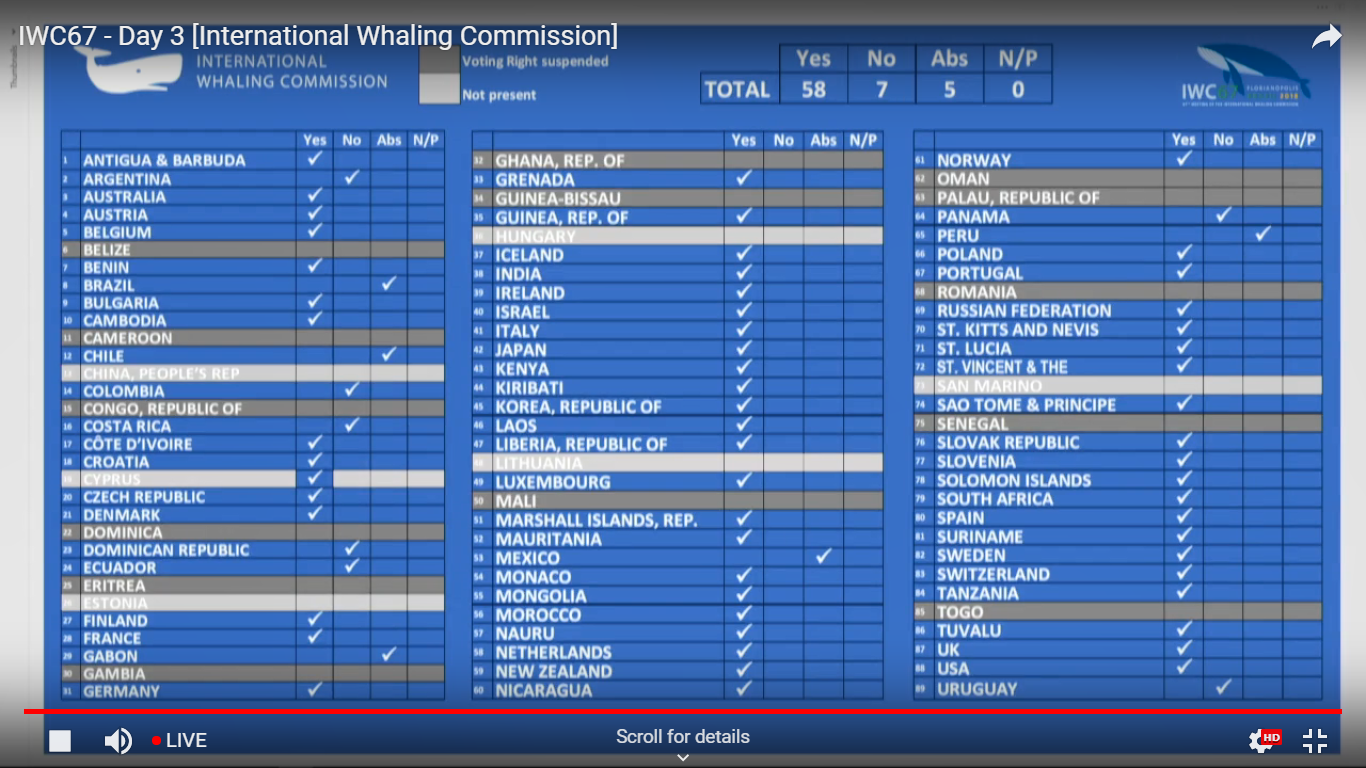

The United States asked for further clarification and asked if Costa Rica would confirm whether it would block the proposal. Costa Rica said it opposed, so there was not consensus. The US then asked for a vote. There were 58 yes votes, 7 no votes, and 5 abstentions, thus achieving the three-fourths majority needed to pass.

The chair then invited proponents to take the floor to explain their votes. Denmark, speaking on behalf of all ASW countries, said how extremely grateful they were that a decision has been reached. Similar comments were made by the United States, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and the Russian Federation.

Argentina explained its vote against the proposal as partly due to concerns expressed by its civil society. It also voiced concerns regarding the automatic renewal issue.

Brazil explained its abstention vote saying that it felt there were unknowns in the proposal related to impacts to whale stocks.

The United Kingdom asked to say a few words, and proceeded to congratulate the proponents and welcome the constructive dialogue, and especially thanked the hunters for their patience. The UK wants to support work to improve the welfare aspects of the ASW hunts and therefore will provide a voluntary contribution of £10,000 for work on the welfare issues and investigation of the stinky whale issue. (“Stinky whale” refers to the fact that in recent years, some landed gray whales have emitted a strong chemical odor.) The announcement was greeted by a round of applause.

The chair then closed the ASW schedule amendment agenda item and broke for coffee.

The chair opened the second session of the day by asking the chair of the Scientific Committee to give a report on whale stocks. The committee chair provided her summary of the committee’s work, reviewing whale species and the threats they face, stock by stock. This was followed by the committee chair’s report on the Scientific Committee’s work on small cetaceans, particularly those facing extreme threats of extinction, including the Yangtze finless porpoise, Mekong dolphin in Cambodia, Ganges river dolphin in India, Irrawaddy dolphin, and Amazon river dolphin. The chair reported that the Scientific Committee had been voicing concerns regarding the threats to the vaquita since the early 1990s, but the committee’s recommendations haven’t been adhered to and the species is facing imminent extinction. The Taiwanese humpback dolphin was also mentioned as facing many threats, including wind farm development, and the committee called for properly prepared environmental impact statements to be completed before development projects are undertaken.

Live captures of Okhotsk Sea orcas are of great concern, and no removals should occur until a full assessment has been made on the two ecotypes believed to exist in the region.

Monaco congratulated the Scientific Committee chair for her report and expressed concern for several species of small cetaceans, especially the vaquita, Maui’s dolphin, and Amazon river dolphin, and encouraged national authorities in the countries inhabited by these cetaceans to adhere to the recommendations of the Scientific Committee. Monaco also stressed that the work of the Scientific Committee gives international credibility to the IWC and urged that all cetaceans should be brought under the IWC’s mandate.

Switzerland thanked the Scientific Committee for its excellent work, and urged the IWC to take action on small cetaceans, especially since some small cetaceans are the most endangered in the world. It highlighted the situation of the vaquita and Maui dolphin in particular, urging the governments of China and New Zealand, respectively to act. (The Maui’s dolphin is native to New Zealand. The vaquita is native to Mexico, but China is a primary import country for totoaba swim bladders—the illegal harvest of which is responsible for many vaquita deaths as bycatch.)

Austria, on behalf of the European Union, also thanked the outgoing Scientific Committee chair for her work. It expressed concerns with the use of small cetaceans for fishing bait. (See AWI report Small Cetaceans, Big Problems.) Further support for the work on small cetaceans was voiced by Argentina, Ghana, and others, with the United Kingdom offering £10,000 to the small cetacean voluntary fund. Finally, Brazil spoke about its efforts to improve the status of small cetaceans in its country, especially related to bycatch and those species in the Amazon region, recognizing the efforts of the eight Amazon countries that work together on protecting the flora and fauna of the Amazon.

Sandra Altherr of German NGO Pro Wildlife spoke on behalf of many conservation NGOs, including AWI, to draw attention to the estimated 100,000 small cetaceans killed in directed hunts and urged range states to report data on species affected and numbers, purpose, and type of takes to the Scientific Committee and the Conservation Committee. In particular, the intervention highlighted the plight of the vaquita, Maui’s dolphin, and Yangtze finless porpoise. The groups also urged the Scientific Committee and the Conservation Committee to undertake a global review of the current status of direct takes of small cetaceans. NGOs also offered a nearly $10,000 donation to the small cetacean voluntary fund.

New Zealand then spoke on the Maui’s dolphin in response to the number of statements raising concerns, acknowledging the comments by the Scientific Committee, and stated that New Zealand is committed to the dolphin’s survival and has a threat management plan in place, as well as restrictions on fishing, seismic surveys, and seabed mineral mining, among other threats. It also reported that it is reviewing the five-year management plan as a priority.

After endorsing the report on small cetaceans, the chair asked the Scientific Committee chair to report on cetacean health and disease, including the threats from morbillivirus and algal blooms on cetaceans, and spoke about a proposed focus session to look at new techniques in monitoring the health of cetaceans. After a comment from Monaco on the importance of this topic, the chair moved on to the next item: stock definition and DNA analysis of whale stocks. The chair of the Scientific Committee spoke about the use of DNA registers and thanked the governments of Japan, Norway, and Iceland for providing information on whale DNA.

The chair then moved to close the meeting for lunch, warning delegates to find a different exit to avoid protesters situated at the main entrance.

After lunch the meeting continued under the “cetacean habitat” agenda item, with a report on the State of the Cetacean Environment Report (SOCER), with which AWI’s Dr. Naomi Rose is very involved. Dr. Lorenzo Rojas Bracho of Mexico then reported on the progress made on the topic of whales in ecosystem functioning, including the plan for a workshop in 2019. AWI’s D.J. Schubert then gave an intervention on behalf of many groups supporting a resolution on the role of whales in ecosystem functioning.

Next, the chair moved on to the ecosystem services resolution. Several countries expressed thanks to Chile for proposing the resolution and support for its passage. Japan, supported by Norway, expressed opposition, claiming that whales shouldn’t be specifically highlighted as an ecosystem component.

After hearing several more interventions both for and against the proposal Chile, as proponent, called for a vote. The Secretariat opened the vote and the resolution passed by simple majority with 40 votes in favor, 23 against, and 7 abstentions.

The chair then moved to agenda item 11, anthropogenic impacts: pollution, marine debris and anthropogenic sound. The Scientific Committee chair gave the committee’s report on its work on these impacts, including the development of a contaminant mapping tool. A resolution was proposed by Brazil on ghost gear entanglement among cetaceans and was widely supported by delegates, including the United States, Grenada, and Korea. Japan said that while it shared the concern for the threat posed by ghost gear, it cannot support the resolution because it believes the issue is beyond the competence of the IWC and would add an unnecessary burden on the IWC Scientific Committee. However, Japan also said that it would not break consensus. Iceland took some issue with the language of the resolution, agreeing with Japan about the competency of other forums on the issue of abandoned fishing gear but also said it would not break consensus. Norway gave an intervention, noting that it has been involved in the collection of ghost fishing gear for many years. It noted that entanglement in fishing gear is, indeed, an issue and that it had worked with the IWC’s Global Whale Entanglement Response Network (GWERN).

After hearing from several more delegates, the chair noted that the chair of the IWC Financial and Administration Committee (the United States) had stated that successful passage of this resolution would not incur increased expenditure by the Scientific Committee. World Animal Protection spoke on behalf of AWI and other groups to support passage of the resolution and called on member states to work with the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. Finally, a representative from the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC) spoke about efforts of his organization to reduce and clean up marine debris.

The chair then asked if there was any country that could not join the consensus after adding one sentence to the resolution offered by Japan that any provision of the resolution should not duplicate the work of other organizations on the same issue. After hearing no opposition, the amended resolution was adopted.

After a coffee break the final session of the day commenced with the outgoing chair of the Scientific Committee speaking about the committee’s work on anthropogenic ocean noise, after which the plenary approved the report. Then the chair of the Conservation Committee gave his report on the committee’s work on ocean noise, including a plan for intercessional work on the issue.

Then came a draft resolution, proposed by Austria on behalf of the European Union, on underwater noise, with a similar addition of a sentence about duplicative work. Japan again stated that the issue was outside the competence of the IWC but would not block consensus. After some comments by Iceland about deletion of a paragraph pertaining to the concurrent UN negotiations on biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdictions (BBNJ), the chair asked if there was consensus to pass the resolution with the addition of a paragraph by Austria on behalf of the EU and the deletion of the BBNJ paragraph. The amended resolution was adopted by consensus.

The meeting then moved on to bycatch, with a report from the Bycatch Working Group, in which AWI’s Kate O’Connell participates. Austria, on behalf of the EU, supported the work, along with several other parties. After approving the report, the meeting moved on to ship strikes. After a discussion by parties, WWF gave a statement on behalf of many NGOs, including AWI, on the growing gravity of the threat to whales now and in the near future from ship strikes, encouraging more work and pledging assistance.

Despite the meeting running very late, the chair announced a 30-minute extension of the session and proposed opening agenda item 12 on the future of the IWC. The chair announced that, as he had mentioned at the private commissioner’s meeting before the plenary, he saw similarities with Japan’s proposal for a way forward and Brazil’s Florianopolis Declaration, which champions the nonconsumptive use of whales. He reported that, although there had been some constructive dialogue, the two items could not be discussed together. He announced that he would open the discussion on Brazil’s proposal, the Florianopolis Declaration. He also asked for input on how to approach the handling of Japan’s package proposal and invited Brazil to present its proposal.

After this, Japan took the floor and stated that, despite changes to the proposal, Japan could not support it because it still contained elements that opposed the sustainable use of whale products. Japan stated that it wants the IWC in the future to respect conservation and sustainable use of whales. Russia then followed, echoing the statement by Japan and said it could not support the declaration, as Russia is a sustainable aboriginal whaling country. Antigua and Barbuda suggested a reconciliation between the Japanese and Brazilian proposals and offered to chair such a group if one is formed. Countries fell along the usual lines regarding the Brazil proposal, with Monaco, the European Union, Chile, the United States, and other pro-whale countries voicing support for a reworked version, and Iceland, Norway, and their allies opposed. More than 30 interventions were heard from governments, an indication of the importance of the issue.

Greenpeace spoke on behalf of several NGOs, including AWI, in support of the Florianopolis Declaration, stressing the changes that have taken place since the whaling convention was drafted and entered into force and noting both the importance of responsible local whale-based tourism for developing economies and the threats whales face today.

The chair opened by giving delegates some updates on the status of the meeting and then turned to agenda item 12, the IWC in the Future, announcing that the meeting would likely go into a night session.

He then asked Brazil to take the floor to speak to the Florianopolis Declaration and Brazil asked for a vote. The motion passed by a simple majority along expected lines, with 40 yes votes, 27 no votes, and 4 abstentions. Abstentions by Switzerland and South Africa were unexpected.

Brazil took the floor to thank parties for their support. Antigua and Barbuda expressed its dissatisfaction with the lack of effort made by the resolution’s proponents to negotiate, calling it “deception, lies, and misleading actions” and calling for the creation of a new organization for the management of whales. St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada made similar statements before the chair moved on with Japan’s proposal.

Japan introduced its Way Forward package, which includes lifting the commercial whaling moratorium, as “the only possible way out for this organization.” The chair then opened the floor to comment. Australia was the first to take the floor and eloquently stated its opposition to a resumption of commercial whaling. This intervention was met with a round of applause.

The United States, speaking as chair of the Financial and Administration committee, gave the committee’s report with regard to the Japan proposal. He stated that the costs, according to the proponent, would ideally be allocated from the commission’s core budget but that they could be funded through voluntary funds if necessary. Regarding work that would be required by the IWC Scientific Committee if the proposal were adopted, on the Revised Management Procedure (RMP) and catch limits, he stated that substantial work had already been done and there would therefore be no more additional financial burden if the proposal passed.

Austria, on behalf of the European Union, reminded delegates that the EU comprises 24 parties that are members of the IWC and who remain committed to the IWC. He said the EU thinks the IWC has achieved a tremendous amount of work in the decades since the moratorium passed and that to preserve what has been achieved, the EU urges restraint to modify the RMP, and therefore the EU opposes an allocation of catch limits on certain stocks—which would overturn the moratorium—and cannot support the creation of new committees. He concluded by stating that moving to simple majority decision-making (called for in Japan’s proposal) would weaken the IWC and be in opposition to the way decisions are made in other international forums. He concluded by stating “there are fundamental differences of opinion between us and therefore we cannot support this proposal.”

Argentina, speaking on behalf of the Buenos Aires Group countries, voiced opposition to the proposal, followed by several countries speaking in favor, including Togo, Benin, Guatemala, Senegal, and Norway. Several countries spoke against, including Monaco (saying Japan was attempting to take the IWC back to the IWC of old, which led to the decimation of the world’s whale stocks), Costa Rica, Uruguay, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, and New Zealand.

Before the coffee break Antigua and Barbuda announced that, with respect to its efforts to negotiate the language of the food security resolution, it would withdraw its request for further negotiation on the matter due to the lack of respect shown by countries in the adoption of the Florianopolis Declaration. With that, the chair closed the session.

After the coffee break the chair invited the remaining speakers to comment on the Japan proposal. The United States opened the session noting its support for consensus where possible, stating that it remains open to Japan and others for discussion. The US thanked Japan but said the US cannot support the proposal as the proposal’s goal is to resume commercial whaling. The moratorium continues to be an effective measure to support whale conservation.

Iceland stated that the IWC is divided. The Japanese proposal is an attempt to get beyond the impasse and that is why Iceland supports it. Several more countries spoke up on both sides and after all the country interventions, the NGOs were allowed to intervene. India stated that is opposed to lifting the moratorium but supported Japan’s proposal to have all votes be on a simple majority, stating that if that had been so for the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary vote, it would have passed.

Finally, the NGOs were allowed to speak, with a pro-whaling NGO starting first in support of the Japanese proposal. Professor Chris Wold of the Lewis and Clark Law Project spoke on the legal deficiencies with the proposal, including how consensus and “super majorities” are used in other international forums rather than simple majorities for decisions with global impact. Finally, Roxana Schteinbarg of Argentinian NGO Whales Conservation Institute gave an intervention on behalf of many NGOs opposing the proposal and schedule amendment.

The chair then invited Japan to respond. After a lengthy response, Japan asked for the agenda item to remain open and the chair suggested it would be kept open until Friday morning.

The chair then asked the representative from New Zealand to step in to report on the meeting of the Whale Killing Methods Working Group, which took place last week. Austria, on behalf of the European Union, thanked her for the report, urged all countries to report their welfare data to the IWC, and commended the IWC on its entanglement and standings response work. Similar comments of support came from several countries, including Monaco, which thanked Norway for trying to minimize times to death. Japan, in response to the requests on provision of data to the IWC, stated that while it used to submit data to the IWC, such data was used against Japan and so it submits this data to other organizations to improve whale killing methods. If Japan’s proposal is adopted, its data-submitting policy could change.

The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (“NAMMCO,” a regional management body established by whaling nations) stated its rational management is based on science and responsible hunting practices. Over the years, NAMMCO stated, it has tried to improve hunting methods for the hunters and for animal welfare. Instantaneous death rates have improved, most notably in Iceland’s fin whale hunt. Struck and lost whales remain an issue it works on and it has developed information to reduce struck and lost incidents. NAMMCO recognizes the conditions under which hunts take place, using different implements.

Claire Bass of Humane Society International, on behalf of AWI and other groups, agreed with the comments of Austria and offered $2,000 toward efforts to improve the animal welfare of hunts. Finally, an Alaskan whaling captain highlighted the fact that the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission continues to improve its whaling equipment to improve efficiency and humaneness of their whaling, despite the impacts of climate change and increasing vessels in their waters. This increase is due to increased training and improved techniques and use of penthrite, and he thanked Norway for assisting in the use of penthrite, but noted its expense, at approximately $1,000 per penthrite projectile.

The chair asked for and received endorsement of the Whale Killing Methods Working Group report and broke for lunch.

The afternoon session started with the chair asking for interventions to be concise given the large number of agenda items still ahead. He then moved onto the next agenda item, special permits. The outgoing chair of the Scientific Committee gave a report of the committee’s work on these controversial permits, noting that there wasn’t agreement on the committee’s findings. The chair then asked the chair of the Special Permits Standing Working Group to give his presentation on the group’s report on special permits. The Australian chair proceeded to give a scathing report of its review, admonishing Japan for failing to provide proper justification for its lethal scientific research. Japan, in response to the report, stated that it took issue with some of the contents of the report.

The United States said that the rules allows the IWC to issue recommendations to Japan and also allows Japan to issue special permits; however, the US urges Japan to pay attention to the words of the commission. New Zealand supported the comments of the US, stressed the importance of the standing group’s findings, and challenged Japan’s contentions that the lethal research is needed in its New Scientific Whale Research Program in the Antarctic Ocean (NEWREP-A), quoting the report that concluded that the need for lethal sampling had not been demonstrated or shown to be useful. Several countries voiced similar concerns, including Argentina, Mexico, and Costa Rica. Senegal and others spoke in support of Japan’s lethal scientific research.

The chair then asked if some effort could be made to reach agreement, whether some or all of the report could be agreed upon, and suggested a statement from Japan regarding its views on the report as part of the meeting report. It was agreed that the meeting would return to the issue on Friday. The chair then asked the outgoing chair of the Scientific Committee to speak to the committee’s report on the procedures used for reviewing special permits.

The chair then moved onto agenda item 15, other conservation issues, and Dr. Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho spoke to each item: Conservation Management Plans, whale watching (including the production of the whale watching handbook mentioned earlier), and the whale watching strategic plan. The United States responded by thanking Dr. Rojas-Bracho and others for their work in helping to bring the handbook to fruition. This view was supported by Austria on behalf of the European Union and several other countries, including Monaco—which challenged Japan and Iceland to provide input for the handbook given their thriving whale watching operations.

The meeting progressed after the coffee break with a report from the outgoing chair of the Scientific Committee on the Southern Ocean Research Partnership – a long term nonlethal scientific research program. She also spoke regarding IWC POWER, another long-standing research program in the North Pacific Ocean supported by Japan. After several delegations spoke in support, the chair moved to enter the report into the record and was supported in doing so.

The chair then moved to the Southern Ocean Sanctuary management plan and the chair of the Conservation Committee gave his report, which included the relevant report from the Scientific Committee. The report was then endorsed and adopted.

The chair then moved to other management issues and started with the Revised Management Procedure—the mathematical procedure whereby catch limits are calculated for removals should the whaling moratorium be lifted. The outgoing Scientific Committee chair gave her committee’s report, including the latest calculations on North Pacific common minke whales and its planned work on Bryde’s whales, and made reference to removals being relevant to bycatch as well as directed hunts. Austria, on behalf of the European Union, pointed out the use of nonapproved RMP catch limits by Norway and Iceland.

Iceland responded to Austria by asking it to take back its comment about Iceland using the wrong RMP tuning level. It said Iceland is staying within the range of tuning levels calculated by the IWC Scientific Committee but that Iceland has chosen which one to use and asked that Austria take back its statement. A discussion on the tuning level ensued, with the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the Scientific Committee chair weighing in. The chair of the Scientific Committee was very clear that the North Atlantic whaling countries were not using the tuning level recommended by the IWC. Finally, the chair moved on and after an NGO intervention on behalf of several groups, including AWI, Japan protested, asking for an apology for singling out Japan for criticism. The chair asked for the two parties to try to work it out outside the meeting.

The meeting then moved onto IWC cooperation with other organizations, including the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (which caused some disagreement between Monaco and Japan about transshipment rights) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). New Zealand commended the IWC executive secretary on the efforts to make contact with other organizations and suggested exploring ways to share the organization’s scientific and technical expertise, such as best practices, while stating that the FAO is the responsible body to manage fisheries. On this, Ghana noted that the FAO has 194 members while the IWC has less, and suggested that it should be the case that these issues are addressed at the FAO rather than here.

The chair then opened the discussions of the next agenda item, the Finance and Administration (F&A) Committee, and said that there are very serious issues and that if they are not addressed, the IWC would run out of funds within seven or eight years. The chair of the F&A Committee raised an issue regarding the Caribbean Environment Program wishing to partner with the IWC and being unable to because of IWC rules. He mentioned the issue of a formal memorandum of understanding that could have financial implications—with the outcome being a decision to look into it further and pursue a more informal agreement.

The Scientific Committee chair presented a paper outlining possible budget cuts, which could be severe. Mexico, as chair of the Conservation Committee, raised the issue of the need to have a Rules of Procedure change discussion in order to have meetings of the Conservation Committee every year. No consensus was reached as to whether to go to annual Conservation Committee meetings. The chair then stated that the Operational Effectiveness Working Group (OEWG) has meetings coming up and could discuss the issue. The chair then thanked the chairs of all the many working groups for their hard work intersessionally.

The vice chair of the Conservation Committee said that there has been important progress by the Bycatch Working Group in tackling the concerns of threats to cetaceans and mentioned the whale watch handbook. The Conservation Committee has established the first strategic plan for a committee of the IWC and, as a result of the plan, members agreed by consensus to hold meeting annually to address issues. The vice chair said that he respects the differences of opinion as to addressing issues that are crucial to the conservation of cetaceans and knows the proposal for annual meetings comes at a challenging time when the IWC is trying to balance its budget. He proposed to change the Rules of Procedure to allow the possibility of annual meetings (IWC67/fa/01) to read “[t]he Conservation Committee may meet annually subject to available funds.” Monaco voiced its support for an annual meeting of the committee.

Antigua and Barbuda stated that the OEWG should consider and look at this in its entirety before making decisions related to the Conservation Committee. After some back and forth, including by Mexico as chair of the committee, it was agreed that the issue would be put to the OEWG as part of the wider governance group discussions.

The discussion moved on to the finance documents 19/4 (Financial Contributions Formula) and 19/5 (Financial Statements and Budget). The chair of the F&A Committee said that there had been no comments or queries on these documents, which cover the final position for the 2016 and 2017 financial years and the forecast position for the 2018 financial year, the commission budget for 2019 and 2020 (including the Scientific Committee Work Programme), and the Budgetary Sub-Committee operations. He reported that the IWC is in a financial crisis and recommended a detailed strategy involving a zero real growth budget option (involving a slight increase in costs to reflect inflation, with a reduction in the Scientific Committee work program and inflationary increases to NGO observer fees). A small group was formed to look at the proposed reductions for the Scientific Committee.

A number of countries endorsed the report and recommendations and some provided suggestion for cost savings. Italy offered 15,000 euros for the Scientific Committee and 5,000 for small cetacean work.

The meeting opened with Australia reporting that there had been a conversation last night with Japan relating to the Special Permit Small Working Group and Japan’s concerns with the report. Agreement had been reached that Japan would dissociate itself from the commission’s view and had prepared a statement for inclusion in the report. The chair accepted the statement and asked if any other member states wanted to add their names to the Japan statement. Numerous pro-whaling countries responded, including Norway, Iceland, and Japan’s usual allies. The chair then closed the agenda item and moved to Japan’s proposal for the way forward.

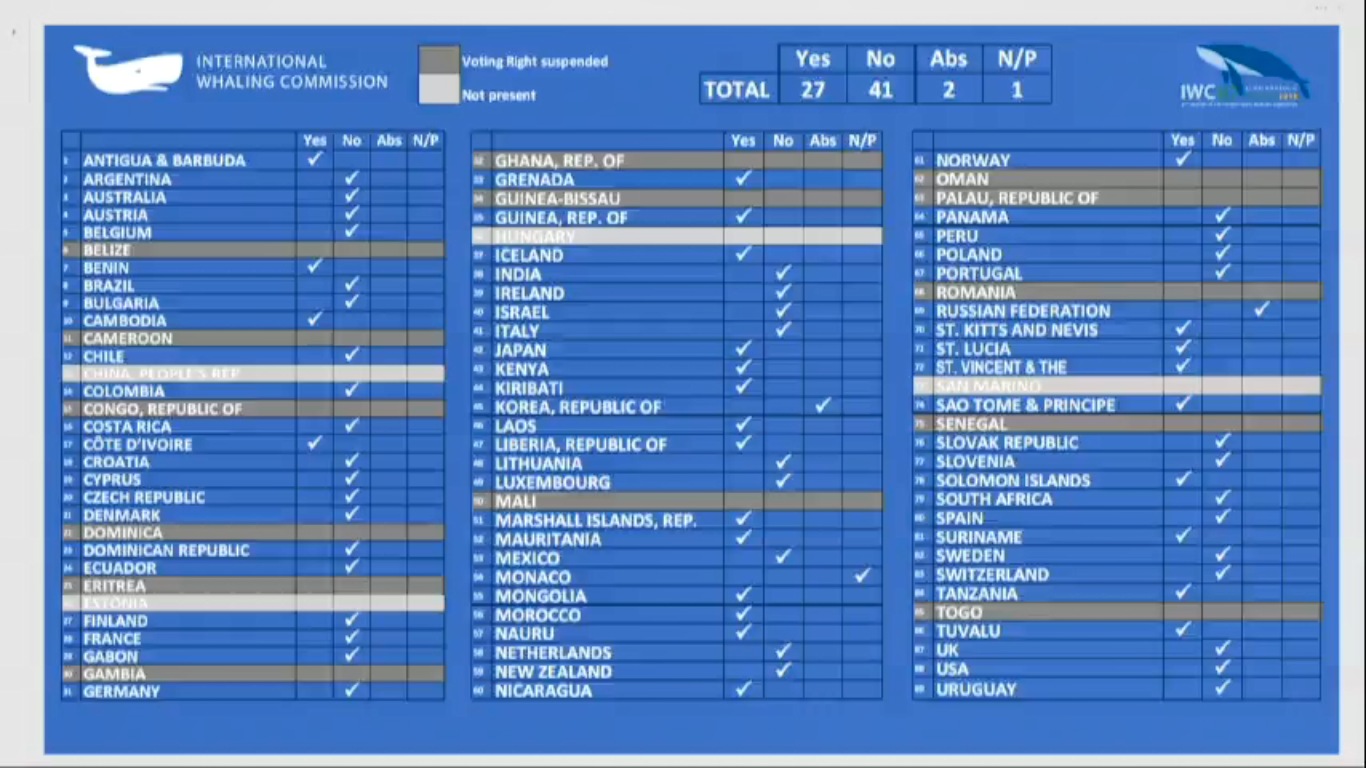

Japan introduced a slightly revised proposal as a package and asked for its adoption. The chair then opened the floor for discussion, urging delegates not to repeat previous interventions. With none, Japan repeated its request for coexistence (pro-whaling and pro-conservation) at the IWC, and asked for a vote. Since the package included a schedule amendment, a three-quarters majority was needed to pass, despite the package including a resolution which, if voted on alone, would only need a simple majority to pass. The secretariat then proceeded with the vote. It failed, with 27 countries voting yes, 41 voting no, and 2 abstentions (the Russian Federation and Korea).

After the vote Denmark took the floor and introduced the Faroe Islands, speaking on behalf of itself and Greenland, saying they supported the sustainable utilization of marine resources, that large whales are part of ecosystem, and that utilization of large whales helps preserve ecosystems and provide food security. He said that NAMMCO is an excellent example of a good marine management organization and that the Faroe Islands and Greenland strongly support Japan’s proposal. The Russian Federation said that it stands for a position of sustainable use and supports scientific research and conservation of large whales. It stated that this vote showed us the sharp split in the IWC and is a point of concern, showing us that we need to spend more time to reach consensus on many items and that Russia’s abstention vote was because it didn’t want to split the IWC.

Austria, on behalf of the European Union, stated its thanks to Japan for its work on the proposal and said that disagreement doesn’t equate to dysfunction. Argentina, on behalf of the Buenos Aires Group, gave a similar explanation for their opposition to Japan’s proposal. Brazil thanked Japan and agreed with Russia, saying that more time is needed to understand each other’s viewpoint.

Japan extended its gratitude to those supporting the “proposal for coexistence,” specifically thanked the Faroe Islands and Greenland for their support, and stated that there was no constructive counterproposal from those in opposition to Japan’s proposal. It said that the vote showed the lack of agreement to coexist and respect for those with different views. It finally thanked the chair for his leadership and said Japan would undertake a fundamental assessment of its position as a member of the IWC, scrutinizing every possible option.

With that, the chair closed that agenda item and moved on to the adoption of subsidiary body reports, those of the Scientific Committee, Working Group on Whale Killing Methods and Welfare Issues, Standing Working Group on Special Permit Programmes, Infractions Sub-committee, Conservation Committee, Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling Sub-committee, Budgetary Sub-committee, and Finance and Administration Committee. All reports were adopted without objection.

The chair then moved to the election of the new chair, Dr. Andrej Bibic of Slovenia, and the representative of Guinea was nominated and approved as vice-chair. The new chair of the Scientific Committee, Robert Suydam of the United States (Alaska North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management), was introduced as the new chair of the Scientific Committee.

The meeting continued after a short break, with discussions on make-up of the IWC Bureau and the Budgetary Sub-committee. The meeting then moved to discussions about future meetings of the IWC and its committees. The chair announced that Kenya is hosting the 2019 Scientific Committee meeting and then opened discussion for the venue for the 68th plenary meeting, in 2020. Slovenia offered to host the meeting.