DAWN ABNEY, National Institutes of Heath, Poolesville, USA

KATHLEEN CONLEE, Humane Society of the United States, Washington, DC, USA

MICHELE CUNNEEN, The AWEN Group, Waltham, USA

NATASHA DOWN, York University, Toronto, Canada

TARA LANG, Animal Behavior Network, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, USA

EMILY PATTERSON-KANE, Purdue University, West Lafayette, USA

EVELYN SKOUMBOURDIS, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA

VIKTOR REINHARDT (Moderator), Animal Welfare Institute, Washington, DC, USA

Address for correspondence: Viktor Reinhardt, 6014 Palmer Drive, Weed, CA 96094, USA

"Does the regular, affectionate interaction with adult animals help the subject overcome the fear of humans, and hence buffer the stress response to being handled during experimental procedures" (Reinhardt)?

"Yes, definitely. I remember when care personnel would go into a big enclosure to catch rhesus monkeys with nets. Often I would join, but while the animals tried to run away from everybody else, some of them would come and sit right next to me, and allow me to put the net gently over them, carefully lift them up and release them into transfer boxes. I had developed a very positive relationship with the monkeys and it was as if they chose to be handled by me rather than the attending personnel whom they mistrusted for good reasons. There was one animal who had been unintentionally hit and injured with the rim of a net during one these notorious capture procedures. She could hardly move after this accident, and we had to take her out of the pen. We were asked by the vet to massage her as part of her rehabilitation. It was really touching how she trusted me, and even fell asleep in my arms while I gently massaged her partially paralyzed body. Fortunately she recovered after a few days and could be returned to her group.

I think an affectionate human-animal relationship makes a huge difference for the animals because it helps them overcome anxiety and fear in disturbing or distressing situations" (Conlee).

"Unfortunately, monkeys have good reason to avoid being touched by a human. That your little female fell asleep while you massaged her, shows that you were an exceptional human for her. She could fully trust you.

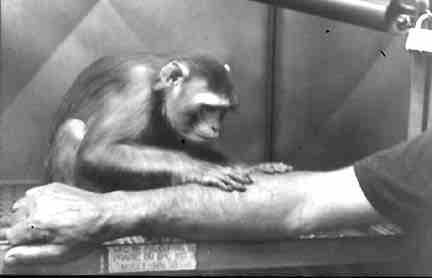

When you have a trust-based relationship with your animals, chances are that they will not only accept your presence but also enjoy being groomed by you, and if you are lucky will even groom you (Figure 1). If you have to handle such an animal during a clinical or experimental procedure, you have a much greater assurance of not being scratched or bitten compared to another animal with whom you have no affectionate relationship but who mistrusts you and tries to get away from you" (Reinhardt).

"I firmly believe that gentle regular interaction can help the animals overcome their fear not only of humans but also of procedures.

Several years ago I worked on studies where we were told that the subjects (several macaque species) would become very ill and, therefore, would require great care from all the techs in order to keep them as comfortable as possible. Because we were doing terminal studies we usually received "recycled" animals who had been in a research laboratory setting for a very, very long time. Many of these monkeys were quite afraid of humans when they arrived in our lab. We were instructed to spend extra time with them so that they would settle down, lose their conditioned fear and develop a bit of trust in us and humans in general. We would sit by their cages, give them treats and try to desensitize them to human contact. There were techs that the animals quickly became much more comfortable with than others, and these techs were the ones who spent the most time "getting to know" the critters, and giving them some affectionate attention. The time we spent proved to be very beneficial when we would have to care for these monkeys later during the study. I will admit that we didn't have a 100% success rate, but we did have animals who would seek our attention and affection after a while. One example that comes to mind is an adult male cyno. He would raise his arms up, much like a small child, to be lifted from his cage to the examination table for treatment. Following treatment he would cry if placed into his cage immediately, because he wanted to spend a little more time outside being held or groomed by the attending technician" (Skoumbourdis).

"I have a few rhesus monkeys in my care. There is one girl, Meka, who loves to have her bum rubbed and her face groomed. She actually asks for it in her way by presenting the body parts she wants to be scratched. We had another monk, Kuaui, who unmistakingly loved human contact. She would pretend to be asleep after a procedure - I would hold the monkeys until they started to regain consciousness and then place them in the recovery cage - so that I would hold her a bit longer. I would watch her squint her eyes, slightly open them to see what was going on, only to quickly close them again if someone was looking at her. She did get what she wanted, and we both enjoyed it (Figure 2).

There is no doubt in my mind that a human-animal bond can help buffer stress, but it all depends on how much the animal subject has gained trust in you" (Down).

"It is difficult to understand why nobody of us - I blame myself also - who cannot but develop an affectionate relationship with the animals in her/his charge never took the trouble to collect data in order to demonstrate "scientifically" that such a relationship not only benefits the animals but also the quality of data that are being collected from them? To conduct such an experiment wouldn't be difficult nor would it have to be expensive. (Reinhardt)

"The answer is easy: We do not get paid or receive appreciation from our institutions for these side projects. That's why our stories are anecdotal" (Cunneen).

"I understand your argument. None of us wants to work extra time with no pay. However, doesn't acute or chronic stress alter the results of experiments and tests? If we can reduce or perhaps even eliminate data-biasing stress reactions by establishing and fostering trust-based relationships with the animals, institutions should find interest in our side projects and support them. I would assume that animals are behaviorally and physiologically more healthy when they are not constantly exposed to anxiety- and fear-inducing encounters with humans. Also, if animals willingly come up to you for a procedure instead of scattering or hiding, the time saved should make up for the time spent bonding early on" (Lang).

"At many institutions you would not be given the time to do this type of work even if you volunteered to stay late. Attempts to refine traditional handling procedures are often seen as an implicit critique of well-established practices that have been handed down from one generation to the other, so they "must" be right.

I agree, the stress resulting form a neutral or negative relationship between investigator/technician and animal is bound to affect the research data collected from the animal subject, but the research industry is not yet taking this methodological flaw seriously. When we try to make the case for it, it has a low or no priority at all.

Discussions of handling/procedural stress and possible refinements are taking place on this type of forum of concerned animal care personnel, but not in academic circles. We in the field are largely "serving" the PIs and the research institutions. This makes it particularly difficult to perform the "real" science in order to prove that our refinement attempts do make a difference not only in terms of improved animal welfare but also in terms of improved scientific methodology.

So I go on making anecdotal observations which I believe make the science better, but I actually don't know for sure" (Cunneen).

"This topic seems to be a great concern for many of us who do the daily hands-on work with the animals. I want to encourage all of you to share some of your personal observations pertaining to our current discussion. It is important to disseminate such information - even if it is not "scientific" - among animal care personnel. This said, let me propose that we submit a summary of our discussion for publication in Animal Technology & Welfare" (Reinhardt).

"Asking us to share our personal observations is like opening up a can of worms for me!

Researchers never decided to get into research because they wanted to work with animals. They are very conceptual in their methods and in their thinking. This alienates them from the creatures they study. What amazes me is that they rarely think about their subjects as sentient beings but focus so much on measurable data. It would benefit the scientific quality of their research greatly if they would take just a bit of extra time to train themselves and their staff in how to properly interact, handle and treat their animals.

If I were to force you to do something for me that you were absolutely terrified of doing, how long would you take to do it and how well would you do it? If I were to help you learn and not be afraid of what I wanted you to do, how much faster and how much better would you be at it? Animals also feel pain and experience fear, so why should they not also be treated with some concern for their well-being?

I have watched people grab, forcibly restrain and manipulate a monkey as if they were dealing with an object, and then wonder why the animal showed so much resistance and signs of distress such as defecating, urinating and squealing. I've also watched monkeys pretty much jump at the prospect of cooperating with a person. Needless to say that the objective of the interaction, e.g., collection of a blood sample, was achieved much faster and without aggressive defense reactions that could have jeopardized the safety of the person.

To many researchers time is money, so they are unwilling to invest any extra time. What they don't realize is, that they would save so much more time in the end, if they would take a little extra time in the beginning" (Down).

"We are all up against a wall here. We all meet the same resistance when it comes to developing positive relationships with the animals in our charge, using positive reinforcement to train the animals to cooperate rather than struggle during procedures, and to offer the animals suitable objects, gadgets and, above all, companionship so that they can better cope with the distress resulting from permanent confinement. Environmental enhancement, affection, and appropriate training techniques are the keys to preventing behavior problems and minimizing or avoiding stress, regardless of where that animal lives. We are the next generation, and our numbers are growing! I am convinced, with persistence and a sincere commitment to animal welfare, we are bound to bring about a change in the "old school" attitudes and husbandry practices. In fact, change is already happening. Discussions like this were a taboo 30 years ago. Today they are quite common and get more and more reflected in the scientific literature and in improved ways animals are housed and handled in laboratories" (Lang).

"Working with PIs and in private industry, I also get frustrated by the rigid limitations to improve traditional handling practices with animals. I see a shift though. Where I am now, there are changes being made. Studies are being modified to work with rather than against the animal subject. However, there is still a lot of "old-school" thinking. It is not easy to implement refinement when the scientists have already been gathering data in the traditional way. We "new-schoolers" are suggesting a different way of collecting data. To convince PIs that their historical data will not be lost, but that the new data will be of greater scientific reliability, requires a lot of firsthand experience, preferably backed up with at least some preliminary data. We may have to make a more concerted effort to demonstrate not only empirically but also scientifically that the changes we are striving for are indeed improvements of scientific methodology" (Patterson-Kane).

"I realize firsthand the battle we are all fighting on behalf of our animals. I agree with Tara that we are the next generation and we do have the chance to improve the situation of the animals we care for on a daily basis. I want to assure you that there are people within the lab animal community working very hard to bring better handling and positive reinforcement training techniques to the forefront of everyone's mind. I think one of the best ways to do this is through grass-roots. We know there is a better way, and if we have the opportunity to prove it - like Natasha did with her rhesus monkey Winnie (Down et al. in this journal vol. 4, pp. 157-161) - then by all means do it, and if possible publish your findings. We are the ones right now doing the dirty work, so we do have more power than we think. Most PIs could care less under which circumstances the samples for their analysis are collected, the main thing is that they receive them in time. Since we are collecting the samples, the quality of the scientific data is dependent to a large extent on our skills and the way we handle the investigator's animals. It is up to us to take advantage of our position and very cautiously but persistently convey our observations for practical improvements to those investigators who are open minded, and before long a refinement technique becomes a standard practice. It's a slow process, but it is already moving in the right direction.

This subject hits a deep nerve with a lot of people on the list serv. This isn't going away as long as we're here. We have an amazing power to make these animals' lives better because of our daily direct contact with them and our firsthand experience with fundamental flaws in the traditional methodology of biomedical research with animals. Just look at the progress we have made in the last 20 years in terms of environmental enrichment versus the traditional barren living quarters, social housing versus individual housing. Quite a number of scientific journals have shifted their focus on these improvements in the housing and handling of animals in laboratories. And these improvements have been developed by people like us for many different species. So keep chipping away at those old crusty investigators and supervisors. When they see what you have accomplished by using your methods, they will be impressed and support your endeavor" (Abney).

"I really like your positive outlook and want to support it. When I first shared my idea of training adult male rhesus macaques to cooperate during blood collection, everybody shook his/her head and politely referred me to the literature which was very explicit: "All monkeys are dangerous" [quote from Laboratory Animal Handbooks 4, 1969]. When I read the literature it became quickly clear to me that nobody had given the animals a real chance to learn how to work with rather than against the human predator. When I gave the animals this chance, positive reinforcement training worked right away not just with one but with many males and, needless to say, also with females. After 19 years, nobody finds a good reason for arguing against the training for the simple reason that is has been published over and over again that the training works.

We are all pushing the cart into the right direction. The more of us push the quicker the cart moves. Keep up the good work for the animals, and by doing so, also for better science" (Reinhardt).

Reproduced with permission of the Institute of Animal Technology.

Published in Animal Technology and Welfare 5 (2), 95-98 (August 2006).