Refined Mouse Handling

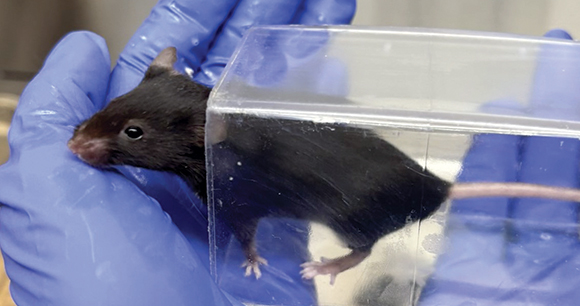

The objective of this project was to introduce tunnel handling—a non-aversive alternative to tail handling—to mice during husbandry and routine handling procedures across a large facility with approximately 12,000 mouse cages. The grant allowed us to purchase clear, square-shaped tunnels and to compensate two staff members to develop a three-phase approach and train 350+ other staff and researchers in tunnel handling.

Phase 1 focused on pilot testing the tunnels in 50 mouse cages. The objectives of this phase were to modify existing husbandry procedures, develop training strategies for staff, and identify potential challenges. Feedback from this phase led to the addition of wooden gnawing blocks to discourage tunnel chewing and to refinements in tunnel placement and cleaning procedures.

Phase 2 expanded the methods to a larger breeding colony with over 100 cages. We further refined training protocols for research staff and were able to assess the broader applicability of this method to both pups and juveniles.

Phase 3 was the most extensive phase of implementation, as it included training for all animal facility and research personnel and the successful, widespread adoption of tunnel handling with all mouse cages.

The implementation of non-aversive handling techniques at our facility represents a major advancement for both animal welfare and research quality and sets a new standard for ethical research practices at McGill University.

by Anna Jimenez, veterinary care manager, and Dr. Marie-Chantal Giroux, director of veterinary and technical services, at McGill University

“Free-Range” Housing for Rats

The aim of our project was to keep the university’s training rats (i.e., those used to train research personnel in handling, injections, and anesthesia) in a “free-range” housing system to provide the animals with more space, choice, and behavioral flexibility compared to traditional cages. The grant allowed us to furnish the playroom and compensate two staff members to develop a positive reinforcement training program that would allow the rats to be caught, when needed, in a low-stress fashion.

The enclosure consisted of a repurposed wire netting aviary (~10.6 m3). The floor was covered with recycled paper bedding and the space furnished with running wheels, litter boxes, climbing structures, and chewing enrichment (e.g., cardboard). This enclosure did allow for a wider behavioral repertoire than standard cages, including climbing, locomotor play, and group rough-and-tumble play.

With stepwise positive reinforcement to handling and capture, the rats voluntarily approached personnel (including strangers) and entered a designated handling area. Switching to a reverse light cycle (i.e., husbandry activities during the dark phase) greatly increased the rats’ motivation to engage with personnel, enter the handling area, and earn food rewards.

After the initial six-month implementation period, the time required for daily husbandry activities for the free-range system was similar to that for standard cages. The rats were litter trained, which greatly simplified cleaning. Personnel found the training process and human-animal interactions rewarding. Future modifications will include more climbing and resting opportunities that make better use of the vertical space in the middle of the enclosure.

by Dr. Sarah Baert, clinical veterinarian, and Michaela Randall, registered laboratory animal technician, at the University of Guelph

Physical Therapy for Animals at a Veterinary School

The aim of the physical therapy program is to reduce muscle atrophy and increase psychological stimulation among dogs, cats, and horses used for teaching at the university’s veterinary school. The grant allowed us to purchase exercise equipment and hire animal rehabilitation specialists to get us started.

Some dogs are really easy to work with and learn quickly, but others are more anxious—at the beginning, even putting their paws on the balance pads was challenging for them. We learned to work with each dog at their own rhythm, and we saw that positive reinforcement training helped staff build a better relationship with the animals. At first, only university staff worked with the dogs, but more recently, we decided to offer the opportunity to students too. We are confident that we will be able to reach our goal of doing physical therapy at least once a week for the dogs and will see the expected results in terms of muscle mass development.

Our main goal for cats was to provide a lot of enrichment and toys so that they could exercise by themselves. We observed that some cats use them, but not the older cats, who usually prefer to sleep! So, we also try to add active playtime with staff every month.

Work with the equine colony only started this past fall. We are focusing on horses who need it the most (2–3 times per week). We are already starting to see a difference in the horses’ muscle mass and a lot more enthusiasm when we go get them for their training!

by Dr. Kathy Lapointe, clinical veterinarian at the University of Montreal